- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

Students

Students

Huaca Cortada

FIRST REPORTS AND RESEARCH

Jose Alva y Augusto Bazán

The El Brujo Archaeological Complex, located on the coast of the Chicama river valley, is an extensive settlement whose first human occupations date back to 14 thousand years before the present. Within this prolix social history, the Huaca Cortada (or El Brujo), located in the extreme northwest of the complex and a few meters from the Pacific Ocean, is one of the most outstanding pre-Hispanic constructions due to its ostentatious monumentality, its landscape intimately linked to the sea, and the mentions it has received in the literature from travelers and archaeologists.

The Huaca Cortada measures approximately 100 x 100 meters and reaches about 17 meters in height. Like the Huaca Cao Viejo, it is built entirely with parallelepiped adobes from the Moche period (100-800 AD). The two gigantic cuts or gashes that can be seen on the south façade and which come near the core of the building, unfortunately, are the most outstanding features of this huaca and the reason for its current name.

The oldest records of this building date back to 1868, when Antonio Raimondi arrived in the Chicama Valley, as part of an expedition to the entire country. The Italian naturalist documented that, at that time, Huaca Cortada was called "Huaca Redonda" because the slopes covered, as they do still now, all its contour. It is particularly interesting that the meticulous Raimondi did not mention the two great cuts of the huaca, which suggests that these excavations were made in later years.

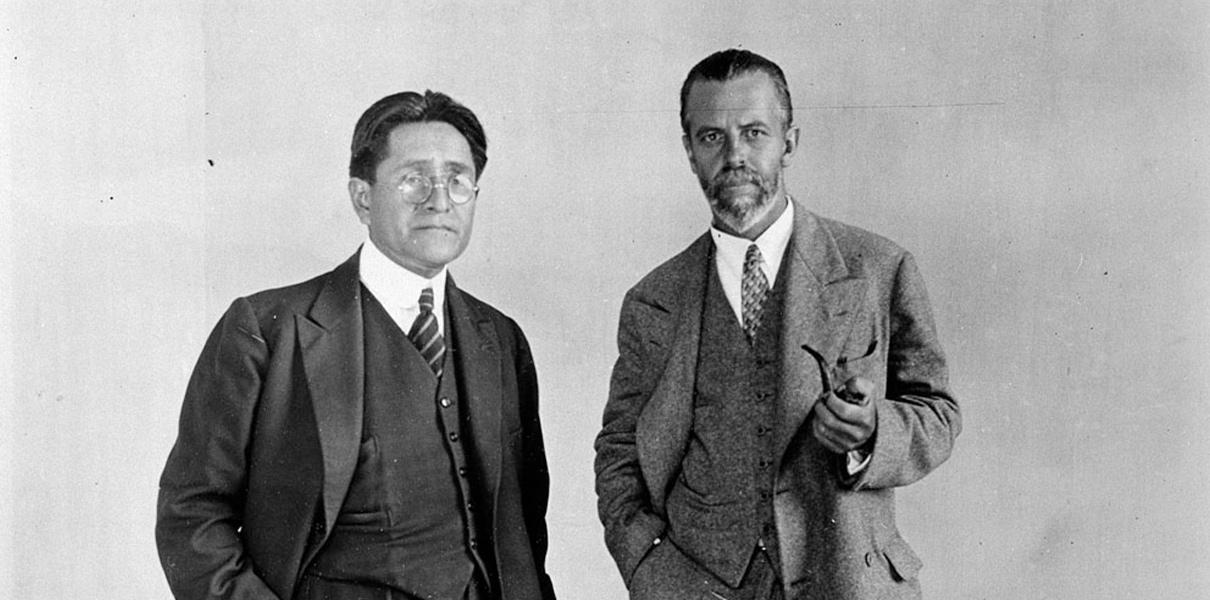

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the development of archeology as a scientific discipline, the Archaeological Complex and what was then called “Huaca El Brujo” were visited by the North American archaeologists Samuel K. Lothrop (1926) and Wendell C. Bennett (1936), who generated the first photographic archives of Huaca Cortada. The photos taken record the gashes on the huaca, the large fillings of adobes, plastered walls and friezes of figures in high relief. Although Lothrop's visit did not leave written information that would allow tracking the dates of the gashes in the building, we can establish a range of 58 years, between his visit and that of Raimondi, as the time in which said damages occurred.

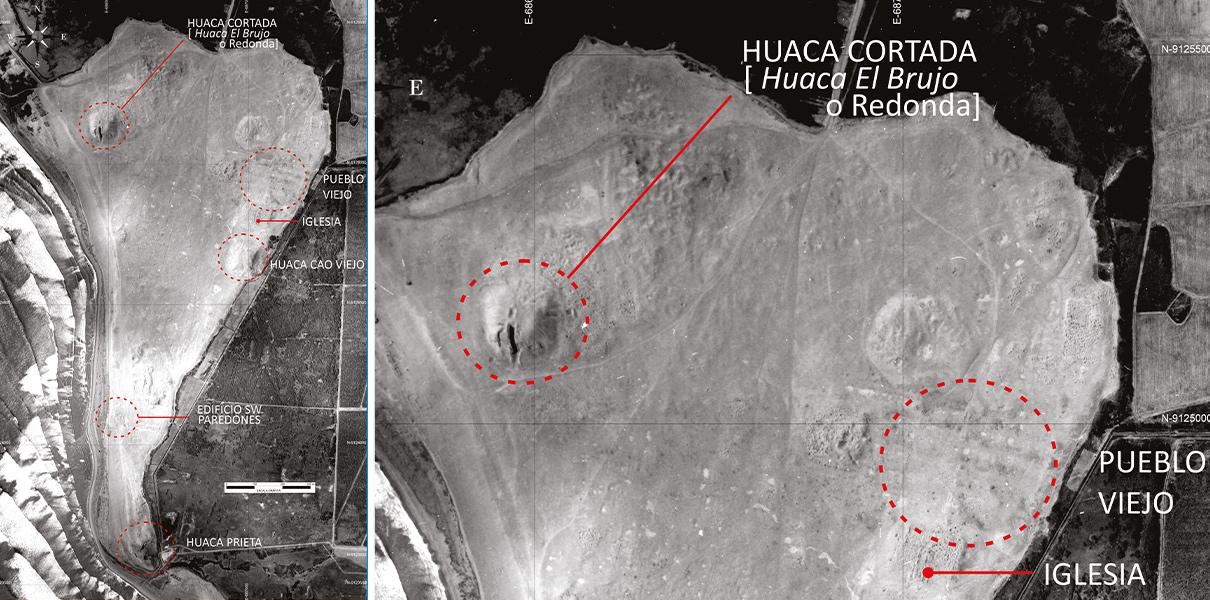

Aerial photo of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex taken by the National Aerial Photography Service (SAN) in 1969.

Julio C. Tello and Alfred L. Kroeber.

At that time, Alfred L. Kroeber, a notable American anthropologist, arrived at the Archaeological Complex in the company of Julio C. Tello, the father of Peruvian archeology. In the 1926 visit, Kroeber collected local accounts that report that the "Huaca El Brujo" gashes were made by the populations neighboring the complex. The objective of these interventions would be, according to these accounts, to extract the well-preserved adobes of the edifice, and not so much the search for the supposed treasures that should exist inside it. This explains the straight and careful profile of, above all, the main excavation.

In recent times, small-scale archaeological interventions were undertaken by Wiese Foundation in order to understand the construction history of the Huaca Cortada, thus named after Junius Bird's excavations at Huaca Prieta (1949). This is how the construction sequence of the monument was identified, based on the profiles exposed by the largest gash (45 meters long and 5 meters wide). For this reason, it is understood that the Huaca Cortada had a constant process of architectural growth through the construction technique of Interlocked Adobe Blocks (BAT), organized sets of parallelepiped adobes that are recognized in Huaca Cao Viejo for covering the previous levels of use. Each major construction phase of the building was related to a new façade in a stepped manner, making the huaca grow larger both upwards and to the sides.

The friezes, recorded at the beginning of the 20th century, are polychrome images in high relief in a clear Moche style. Given their style and stratigraphic position, they correspond to the earliest phases of the Huaca Cortada. The designs depicted on these walls are diagonal stripes with representations of Peruvian catfish (Trichomycterus sp.) With interspersed colors. These wall figures and their configuration are recurrent in the early phases of Huaca Cao Viejo, specifically at the southern end of the Ray and Manta ray Courtyard, and in the Enclosure-Mausoleum of the Lady of Cao.

All these evidences, as far as they allows us to understand it, indicate that Huaca Cortada and Huaca Cao Viejo are in good measure contemporary buildings, and that the functioning of both was probably complementary, around political, religious and even economic activities during the Moche period.

The work carried out by Wiese Foundation, based on the exposed profiles of the Huaca Cortada, as well as the early evidence described in this article, have made it possible to identify the grave state of conservation of the monument. The outermost construction phase is seriously damaged by the breeze and the salinity of the sea, which is only a few meters away. The excavation, evidently, has not only destroyed the most recent parts, but has also penetrated the earliest phases of the building, causing moisture to enter and affect the depths of the building, affecting its structural stability. Considering the great potential for information and knowledge that it contains, unveiling the secrets of the Huaca Cortada implies intervening it in an integral way. A great effort that involves a sustained conservation project that goes hand in hand with scientific research, and a subsequent and permanent work of maintenance, monitoring and enhancement.

Figure 1. View of one of the friezes recorded in the gash of Huaca Cortada.

Photo taken by Samuel L. Lothrop (Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology at Harvard University).

Figure 2. Drawing of one of the friezes documented at Huaca Cortada. CAEB Archive / Wiese Foundation.

Bibliography, Bennett, Wendell C.

- 1939 “Archaeology of the North Coast of Peru. An account of exploration and excavation in Viru and Lambayeque Valleys”. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. Volume XXXVII, part 1. New York City: The American Museum of Natural History. Bird, Junius B. y John Hyslop

- 1985 The Preceramic Excavations at the Huaca Prieta, Chicama Valley, Peru. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Volume 62, part 1. New York: The American Museum of Natural History.Franco, Régulo; César Gálvez y Antonio Murga.

- 2002 “The Huaca El Brujo. Architecture and Iconography”. Arkinka 85: 86-97. Kroeber, Alfred L.