- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Exploring the ancient art of basketry: Tradition and Culture in Every Strand

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Katerine Albornoz

Exploring the ancient art of basketry: Tradition and Culture in Every Strand

Segundo Chuquipoma: "Craftsmanship is not something inert, but something full of utility."

By Katerine Albornoz

Introduction

Throughout the history of human development, we have carried out different economic activities, including textiles. This endeavor involved the creation of various garments and objects intended for specific functions, such as protection and shelter against natural inclemency. To achieve it, a range of techniques, tools and materials were developed that made its realization possible. Among these techniques is basketry, a topic that we will address on this occasion based on information from archaeological research, as well as its contemporary practice.

Basketry: Weaving with hard fibers

Textile-making had its beginnings in seemingly simple works. Nonetheless, it required the use of a special knowledge set and materials, as in the case of basketry. This activity implies manual weaving of vegetable fibers, without resorting to a loom or any other tool.

The earliest evidence of this work has been found at a number of sites in Moravia, Czech Republic, dated to between 27000 – 29000 cal. BP (Adovasio, 2010).

Various studies (Asencios, 2009; Bird, 1985; Bueno M, 1998) carried out in Peru have shown that basketry has been widely practiced since the preceramic period. The main reference that we have are the archaeological remains recovered in Huaca Prieta, Chicama Valley, dated between 10,600 - 11,159 cal. BP (Dillehay, 2017). As the years went by, the different societies perfected their economic activities, including basketry, which resulted in improvements in manufacturing techniques, among other aspects.

Currently, basketry is considered an artisanal work that is part of our pre-Hispanic legacy.

Basketry as an artisanal work

As mentioned above, basketry is the art of weaving hard fibers to create objects such as baskets, floor mats, furniture, hats, sandals, among others. The artisans currently working in this field are knowledgeable about the various materials and techniques that are needed for its elaboration. To better understand what materials are used, we will first define what fibers are and which ones they are.

What are fibers?

Fibers are long, thin filaments that make up a tissue or object. Fibers are classified into two categories: natural and artificial. On this occasion, we will focus on fibers of natural origin (Vidal & Hormazábal, 2016). Within natural fibers, there is a subclassification, which is composed of:

1. Plant-based fiber

2. Animal-based fiber

The textile activity has made use of both types of fibers. However, basketry has focused on the use of fibers with particular characteristics, such as vegetable fiber.

Vegetable fiber can be obtained from different parts of a plant, such as the seed, stem, leaf or fruit (Bastiand Atto, 2000). Depending on the part from which it is extracted, it is divided into soft and hard fibers. In the case of basketry, the fiber used comes from the stem. Some of the most recognized include: flax, hemp, jute, ramie, laurel and willow, among others (Mincetur, 2008). These fibers represent the fundamental raw material for the elaboration of garments, utility or decorative objects. Then, the raw material must be processed for further interweaving.

A conversation with the artisan

To learn a little more about this work, we conducted an interview with Mr. Segundo Chuquipoma, one of the artisans of the district of Magdalena de Cao, located in the province of Ascope, Trujillo.

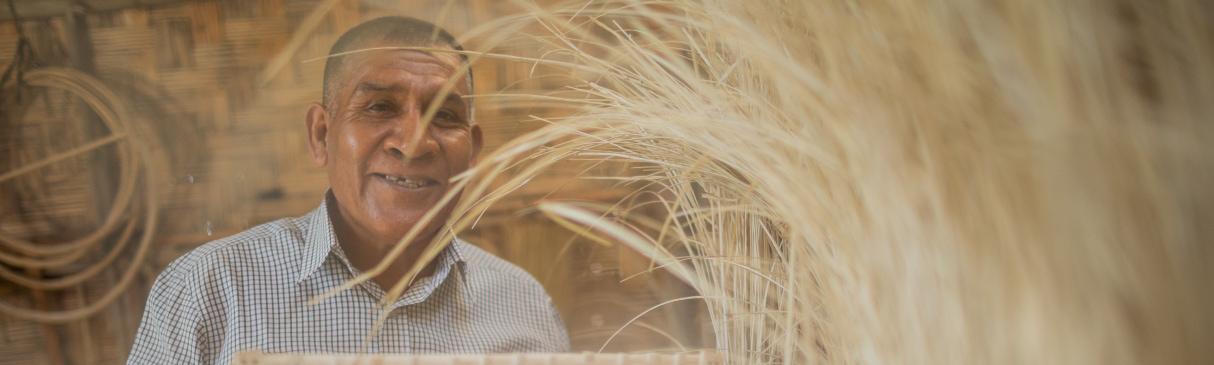

Photo 1. Mr. Segundo Chuquipoma, artisan of Magdalena de Cao.

KA: How did you become interested in basketry?

SC: It all started with my curiosity as I saw a friend create beautiful baskets when I was between 13 and 14 years old. So, I decided to ask him: "Buddy, could you teach me how to make those baskets?" I started learning how to make a little basket that didn't turn out quite right. Then I made another one, which improved a little. And thus, I continued perfecting my skill in the craftsmanship. As I improved my skill and was able to create higher-quality baskets, I broadened my scope and began to make toys, baskets, flower holders and a variety of objects.

KA: Did any other members of your family become interested in learning about basketry?

SC: I was born in the township of Pomabamba, in the district of Jesus, in Cajamarca. My family was mainly dedicated to agriculture. However, my grandmother and mother used to spin, and my father knitted ponchos. One of my sisters became interested in the art of weaving. I come from a family of weavers from the countryside. They were not dedicated to selling what they made, but rather to do it for their personal use. Despite this, I was the only one who was curious about basketry and developed my way of working. Over time, this skill has helped me get ahead and I have had the opportunity to travel to different departments of Peru.

KA: What motivates you to continue practicing this artisanal work?

SC: I depend on my artisanal work for my livelihood. Craftsmanship can generate all kinds of objects from large to small. It is not an obsolete trade, but rather has a real and useful purpose. From the moment I started learning this skill, I always had in mind that it represented an opportunity to create something meaningful.

KA: What would be the main steps to follow?

SC: The beginning of the work goes according to the nature of the object, whether it is a basket or a hamper. To start, we take the measurements of the object and design it according to these dimensions. Next, we select the adequate material (the fibers that we will use) based on that design. The next step involves the search and collection of the materials that we are going to employ. Then, we begin the process of preparing the material, which includes rigorous cleaning. In some cases, as with laurel, it is necessary to subject it to a burning process.

The cleaning involves first peeling the stem, then rinsing it, and subsequently dividing it into smaller segments. Finally, we proceed to brush it. Each of the filaments that make up the piece must be subjected to this process. Once we complete the cleaning, we let the materials dry in the shade before moving on to the interweaving process. This is a laborious and time-consuming procedure.

Final Thoughts

As we have observed, basketry is an economic and social practice with a long history in the development of man in different societies. Today, as Mr. Chuquipoma points out, "handicrafts are forgotten", although it continues to be an essential source of income for many artisans. The knowledge acquired, whether through family inheritance, teachings from acquaintances or own experiences, contributes to the cultural legacy that endures.

However, our society is undergoing constant transformations, which raises a debate about how to keep our past alive and present. In response to this reality, associations, collectives and initiatives have emerged, both among public and private institutions, which seek to create venues to promote, disseminate and put into practice this know-how.

Bibliography

Adovasio, J. M. (2010). Basketry Technology. A guide to identification and analysis (Second edition).

Asencios, R. (2009). Investigations of the Shicras in the preceramic site of Cerro Lampay [Thesis]. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Bastiand Atto, M. S. (2000). Pre-Hispanic textile production. Social Research, 5, 125–144.

Bird, J. B. (1985). The preceramic excavations at The Huaca Prieta Chicama Valley, Peru (J. Hyslop & M. Dimitrijevic Skinner, Eds.; Vol. 62).

Bueno M, A. (1998). The site of La Galgada: archaeological excavations in the North and South Mounds. Investigaciones Sociales, 2, 77–91.

Dillehay, T. (2017). Where the land meets the sea: fourteen millennia of human history at Huaca Prieta, Peru (T. Dillehay, Ed.; Primera). Library of Congress.

Mincetur. (2008). Artisan tourist guide of Peru.

Vidal, G., & Hormazábal, S. (2016). Vegetable fibers and their applications.

Researchers , outstanding news