- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Artisanal Work series: A Journey through pre-Hispanic metallurgy

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Katerine Albornoz

By Katerine Albornoz

A visit to the museums in the north of the country immerses us in a fascinating journey through the vestiges inherited by our ancestors, among which the exquisite funerary trousseaus of the Mochica or Lambayeque societies stand out. When touring the exhibition halls of these museums, we face the reality that we can only contemplate the final result of a meticulous production process, carried out by specialists through time. In this note, we set out to clarify a little the information about pre-Hispanic metallurgy, from the extraction of the mineral to the production of the goldsmithing object, focusing on one of the decorative techniques practiced by our ancestors: embossing.

A glance at the Past: Exploring the use of metal in the pre-Hispanic epoch

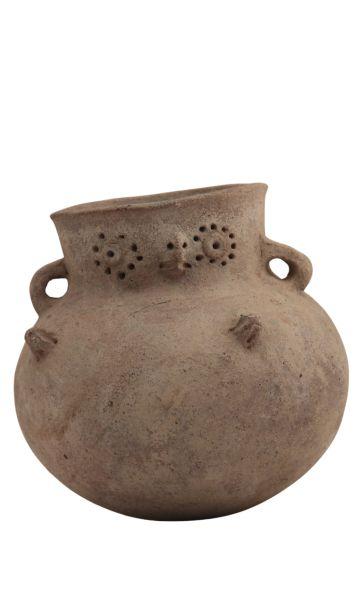

According to studies on the development of metallurgy, this practice dates back to the Late Archaic Period, which spans approximately from 2155 to 1936 B.C. Initially, the first metal used to make objects was native gold, as has been demonstrated at an archaeological site in the province of Collao, in Puno. However, continued metalworking has also been documented, evidenced by gold leaf discovered at Waywaka, a location in Andahuaylas, in the Southern Peruvian Andes. Also, small pieces of gold dating from the Formative Period in the Central Andes have been found, located on the North Central Coast and the North Central Sierra of the present-day Peruvian territory (see image 1) (Grossman, 1972; Vetter & Bazán, 2022).

Metallurgical activity seems to have advanced technologically before the development of the societies that emerged in later periods. Although we cannot precisely determine the exact beginning of this progress and how it was accomplished, there is evidence to indicate that during the Formative Period, approximately between 800 and 500/600 B.C., the mixing of different minerals was being explored in order to produce new materials with specific characteristics. This information is derived from evidence discovered in places such as Kuntur Wasi (Vetter & Bazán, 2022).

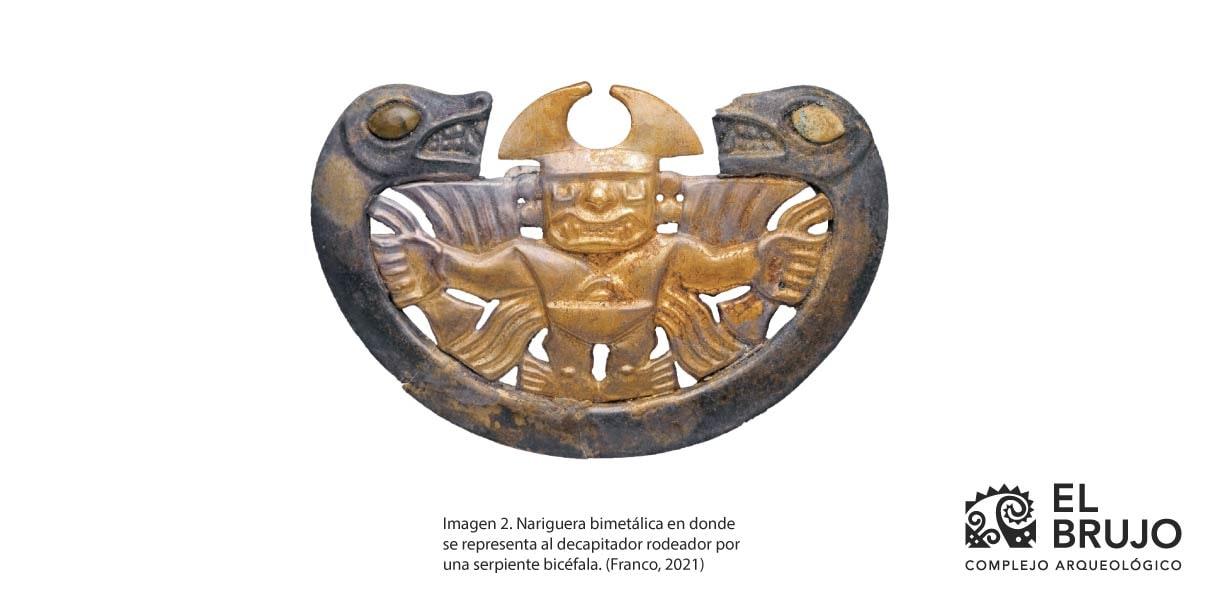

Throughout the different pre-Hispanic periods, notable advances in technology, manufacturing methods, and decorative techniques have been recorded. These advances have been documented through evidence found in societies that flourished in later times, such as the Mochica, Lambayeque, Wari and Inca. These societies are recognized for their significant achievements during their periods of development and expansion (see images 2 and 3).

From the study of the Mochica society, important information has been obtained on the metallurgical techniques used, such as copper-gilding, granulation, lost wax, filigree, among others, as well as decorative techniques such as embossing, inlaying of semiprecious stones and re-gilding to make vessels (Alva, 1988; Carcedo, 1992; Vetter, 2007). This variety of techniques has been observed in the objects found in funerary trousseaus recovered in tombs in the valleys of Lambayeque and Chicama (see image 4) (Shimada, 1994; Torrealva Álvarez et al., 2014). These pieces are currently on display in two museums in northern Peru: the Museum of Royal Tombs and the Cao Museum.

Exploring the pre-Hispanic epoch: Manufacture and Goldsmithing Techniques

The manufacture of metal objects represented a notable technological progress, resulting from social changes and the specialization of work, which demanded technical knowledge and specific training. This process implies an extensive sequence of activities that will be mentioned succinctly in order to focus on the decorative techniques.

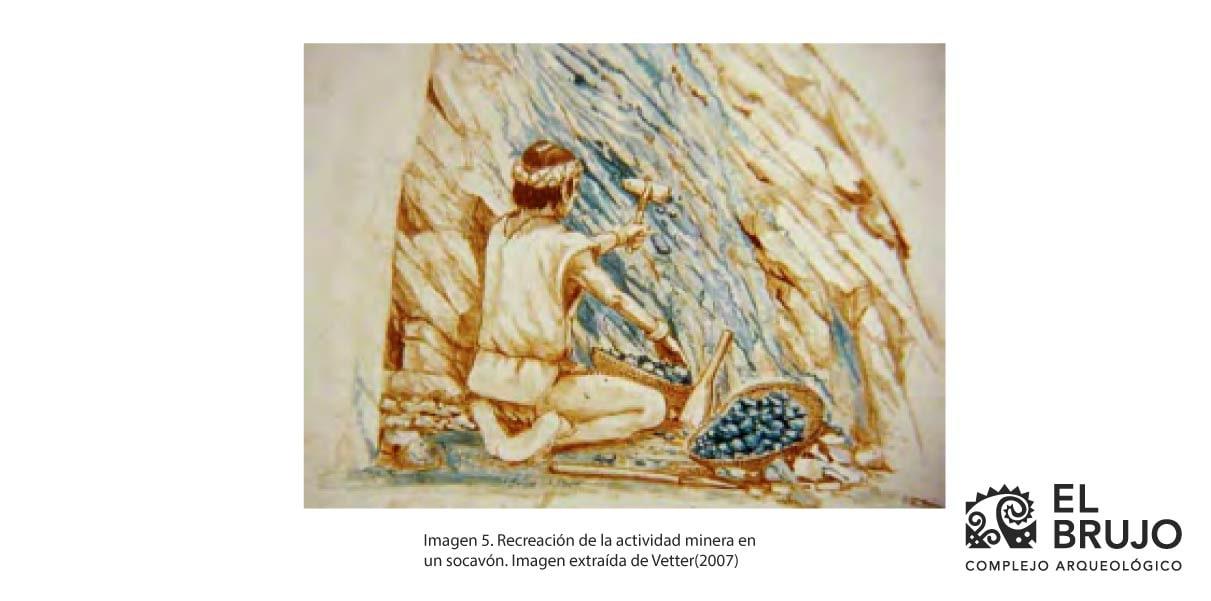

Extraction of the ore

Based on the research conducted on the mineral extractive activity, currently known as mining, it has been documented that both the northern coastal region and the mountainous area are rich in copper deposits (Lechtman, 1976). The extraction of these minerals was carried out by digging in shafts or tunnels of small dimensions (see image 5) (Sánchez & Delli-Zotti, 1994). In order to carry out this activity, specific tools were used, such as stone hammers with wooden handles. Also, the use of leather bags for the transport and storage of the extracted ore has been documented (see images 6 and 7) (Bird, 1975; Brown W & Craig K, 1994).

From ore to metal

The next step implies the transformation of the extracted ore by subjecting it to a controlled temperature in specific environments, such as smelting furnaces (Carcedo, 1992). The research carried out by the team of the archaeological project of Sicán in Batan Grande have contributed significantly to unraveling the enigma of how the ore smelting was conducted. Although the findings made at the site of Huaca del Pueblo in Batán Grande belong to a society of the late period, they provide clues as to how this process may have taken place much earlier (see image 8). Among the most outstanding evidence are rows of remarkably well-preserved furnaces, each with between 3 and 4 kilns, sets of grinding stones and crucibles, as well as ceramic nozzles. Also, it has been determined that the fuel used was carob charcoal, from a local tree (Shimada, 1994).

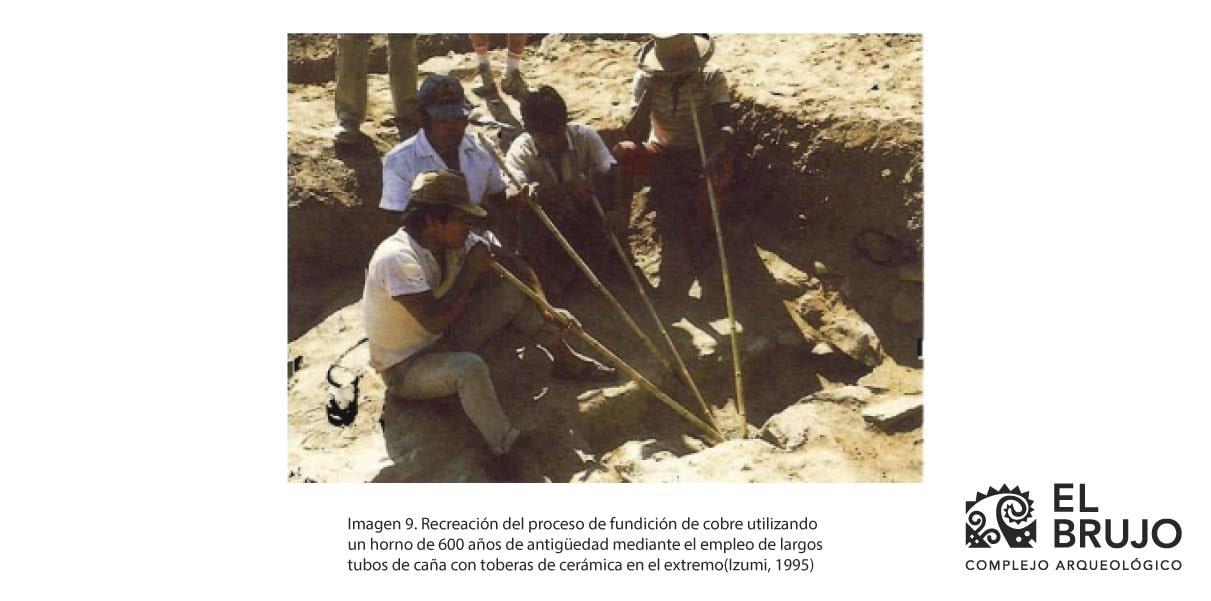

Archaeometric studies have revealed that the temperature needed for melting in the furnace must have been between 1000°C and 1100°C, and this temperature was maintained by the action of the human lungs through long blowing tubes, known as nozzles (see image 9) (Shimada, 1995).

Aside from having specific tools, this process required a profound understanding of the physical properties of the minerals and an environment that provided the right conditions. Here are some essential considerations for this crucial stage, which are generally addressed in this section. Several investigations have explored the presence and attributes of smelting furnaces, the study of the alloys made, and more, thus contributing to a greater understanding in this ambit (Aimi et al., 2016; Brooks & Parodi, 2012; Lechtman, 1976; Vetter, 2007).

The end-result of this stage is a metal cake or metal ingot, which marks the beginning of the next phase: the goldsmith's work.

From the metal to the object: Goldsmithing

In the introduction, we mentioned that, when visiting a museum, we find ourselves admiring the metal objects, impressed by the meticulous detail and finish that they have. It is at this point that we appreciate the hard work carried out by goldsmiths, who employ a variety of manufacturing and decorative techniques to transform metal into the beautiful objects that we observe (Vetter, 2007). As in any specialized work, both in the past and in the present, it is fundamental to have appropriate tools and an adequate environment, such as goldsmithing workshops (Uceda C & Rengifo C, 2006). These tools include chisels, molds, punches, burins, hammers, and various others (Carcedo et al., 2004; Carcedo & Vetter, 2000; Hocquenghem & Parodi, 2005).

Manufacturing Techniques

LAMINATION

In the central Andean regions, one of the oldest and most prevalent techniques is lamination. In this process, the craftsman would take an ingot and strike it with a hammer, keeping it constantly hot to prevent it from cracking due to the pressure of the hammering. Considering the utility or purpose intended for the final object, it was necessary to make the sheet according to such function. For example, the making of a sheet as a component of a headdress differs significantly from the making of a sheet designed to support weight (see image 10) (Vetter, 2007).

Once the sheet was made, it was possible to use a variety of techniques to transform it into a different object, such as embossing or decorating it. For that, they had decorative techniques such as chiseling and openwork, among others.

Decorative techniques

CHISELING

The chiseling technique consists in creating designs on a flat surface using a chisel and hammer blows, thus achieving the desired design.

EMBOSSING

This technique implies tracing a pattern on the surface of a sheet, which must be placed on a flat and smooth base. This allows that, when applying pressure with a chisel onto the metal, a pronounced relief is achieved on the back of the sheet. Subsequently, work is done on the face where the embossed design is located, applying pressure to the marked areas to enhance the effect. This process of alternating chiseling on both sides continues until the artisan determines that the piece has been completed (see image 11).

Returning to our present

Metallurgy and goldsmithing have been present since the early stages of human development. However, due to various factors, these techniques and knowledge have been conserved mainly within a few communities, though with certain differences. In this context, we have chosen to contact the artisan Rosa Ruiz Caipo from Casa Grande, in the Chicama Valley, Ascope. She is an expert in the decorative technique of embossing. During our conversation, she shared with us how she came to be an artisan and how she has kept this tradition alive in her community.

Conversation with the artisan

KA: How did your journey into artisanal work begin?

RR: "Since I was little, I have been immersed in the world of artisanal work thanks to my family. My parents are originally from Huamachuco. My father and his relatives were engaged in wood carving, especially plates and other objects of daily use. Also, my father worked in a sugar cane company. My mother was dedicated to weaving, a skill that she learned from her own mother, who was a loom weaver. From an early age, I have been interested in artisanal work thanks to my family environment. In my career, I have had the opportunity to explore various crafts and have developed a particular interest in the art of embossing on aluminum."

KA: Currently, how can this knowledge of the embossing technique contribute to the community of Casa Grande?

RC: "In this case, I use the aluminum embossing technique to preserve ancient elements, such as the traditional skills of people in their daily chores, and that's what I reflect in my work. For example, one of my projects focuses on portraying those who make mats or fabrics of the Mochica culture. This knowledge can not only help to rescue and valorize local customs and culture, but it can also spark interest among young people and provide them with a source of income. Not all work is limited to the crops, but also involves skills such as painting, textiles, and more."

Final Thoughts

We begin this text by commenting on visits to museums, highlighting the perception of objects created by people who were part of a specific society. Now, we turn our attention to the present, focusing on contemporary events such as craft fairs, for example, Ruraq Maki, exhibitions in art galleries, and also religious settings such as churches. In these places one can occasionally see works made of metal, such as earrings and portraits in sheets of this material, among other objects. Becoming admirers represents the first step towards appreciating this work. Delving into the technique and its history through these creations leads us to reflect on the continuity and evolution of the artistic knowledge applied by our ancestors and preserved by contemporary artisans. Recognizing the relevance of our cultural heritage thus becomes a fundamental aspect for our progress as a society, interpreting it as an opportunity for preservation, continuity and development.

Bibliography

Aimi, A., Makowski, K., & Perassi, E. (2016). Lambayeque: New horizons of Peruvian archaeology (A. Aimi, K. Makowski, & E. Perassi, Eds.; First edition).

Alva, W. (1988). Discovering the New World’s Richest Unlooted Tomb. National Geographic, 174, 510–549.

Bird, J. (1975). The copper man, a prehistoric miner from northern Chile and his tools. Bulletin of the Archaeological Museum of La Serena, 16, 77–132.

Brooks, W. E., & Vetter, L. (2012). Ancient lead smelter at the Inca site of Curamba, department of Apurimac, Peru. Bulletin de I'Institut Francais d'Études Andines, 41(2), 197–208.

Brown W, K., & Craig K, A. (1994). Silver mining at Huantajaya, Viceroyalty of Peru. In A. Craig K & R. West C (Eds.), In quest of mineral wealth: aboriginal and colonial mining and metallurgy in Spanish America (Vol. 33, p. 303). Geoscience Publications, Dept. of Geography and Anthropology.

Carcedo, P. (1992). Pre-Columbian metallurgy: manufacture and techniques in the goldsmithing of Sicán. In Oro del Antiguo Perú (pp. 265–305). Banco de Crédito del Perú en la Cultura.

Carcedo, P., & Vetter, L. (2000). Instruments used for the manufacture of metal pieces for the Inca period. Baessler Archive, 50, 47–66.

Carcedo, P., Vetter, L., & Magdalena Diez Canseco. (2004). Anthropomorphic effigy-vessels: an example of central coast goldsmithing during the late intermediate period and the late horizon. Boletín de Arqueología, 8, 151–189.

Grossman, J. (1972). An Ancient Gold Worker’s Tool Kit: The Earliest Metal Technology in Peru. Archaeology, 25, 270–275.

Hocquenghem, A. M., & Vetter, L. (2005). The pre-Hispanic metal points and grilles in the Andes and their continuity up to the present. Bulletin de I'Institut Francais d'Études Andines, 34(2), 141–159.

Lechtman, H. (1976). A Metallurgical Site Survey in the Peruvian Andes. Journal of Field Archaeology, 3(1), 1–42.

Sánchez, J., & Delli-Zotti, G. (1994). American Mining and European Mining, 1750 - 1820. A comparative perspective. In A. K. Craig & R. C. West (Eds.), In quest of mineral wealth: aboriginal and colonial mining and metallurgy in Spanish America (Vol. 33, p. 205). Geoscience Publications, Dept. of Geography and Anthropology.

Shimada, I. (1994). Pre-Hispanic metallurgy and mining in the Andes: recent advances and future tasks. In A. K. Craig & R. C. West (Eds.), In quest of mineral wealth: aboriginal and colonial mining and metallurgy in Spanish America (Vol. 33, pp. 37–73). Geoscience Publications, Dept. of Geography and Anthropology.

Shimada, I. (1995). Sicán Culture: God, Wealth and Power on the North Coast of Peru. Foundation of Banco Continental for the Promotion of Education and Culture.

Torrealva Álvarez, J., Bernuy Quiroga, K., Castañeda Murga, J., Campana Delgado, C., Castillo Reyes, S., Cornejo Rivera, I., Curo Chambergo, M., Delgado Elías, B., Fernández Manayalle, M., Franco Jordán, R., Gálvez Mora, C., Alvarado, F., D. Klaus, H., Martinez Fiestas, J., Muno, S., Narváez Vargas, A., Klaus, D., Fiestas, J. M., Muno, S., ... Rosas, J. (2014). Lambayeque Culture: In the context of the north coast of Peru, Proceedings of the first and second colloquium. Editors (J. C. Fernández Alvarado & C. E. Wester La Torre, Eds.; First, pp. 139–165).

Uceda C, S., & Rengifo C, C. (2006). The specialization of work: theory and archaeology. The case of the Mochica goldsmiths. Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines, 35, 149–185.

Vetter, L. (2007). The role of indigenous silversmiths in the early colonial era of the viceroyalty of Peru [Thesis]. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Vetter, L., & Bazán, A. (2022). Gold Artifact Production During the Central Andean Formative Period: New Evidence from Chavín de Huántar and Caballete, Perú. In Reverse Engineering of Ancient Metals (pp. 215–348). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72842-7_12

Researchers , outstanding news