- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Loom weaving, an ancestral technique.

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Katerine Albornoz

By Katerine Albornoz

Currently, we recognize as part of our historical-cultural legacy the economic activity known as Textile-Making There are different anthropological, ethnographic and archaeological research undertakings that highlight its importance in social, religious, political and cultural development. However, what do we know about this activity and the techniques employed? On this occasion, we will delve into one of the techniques used in pre-Hispanic times and its presence nowadays: we are referring to the backstrap loom technique.

What is textile-making?

It is the textile production process linked to pre-Hispanic societies, up to the present day, with the purpose of making garments (apparel), cloaks, textile objects such as pillows, among others, in an artisanal manner. It begins with the selection and processing of the raw material, followed by the crafting of the yarn for the fabric. Subsequently, the threads are put in place to employ the loom technique (Bastiand Atto, 2000; Vulture, 2000; Carmona, 2006; Quevedo, 2015; Manrique, 1999).

Textiles have two main components: the work process involved in its crafting and all the technology used for it. Moreover, it is a means of building identity, whether it be collective, individual or ethnic, regional, etc. This allows us to identify the provenance, cultural filiation, and social and economic status (Bubba, 2013).

Loom weaving

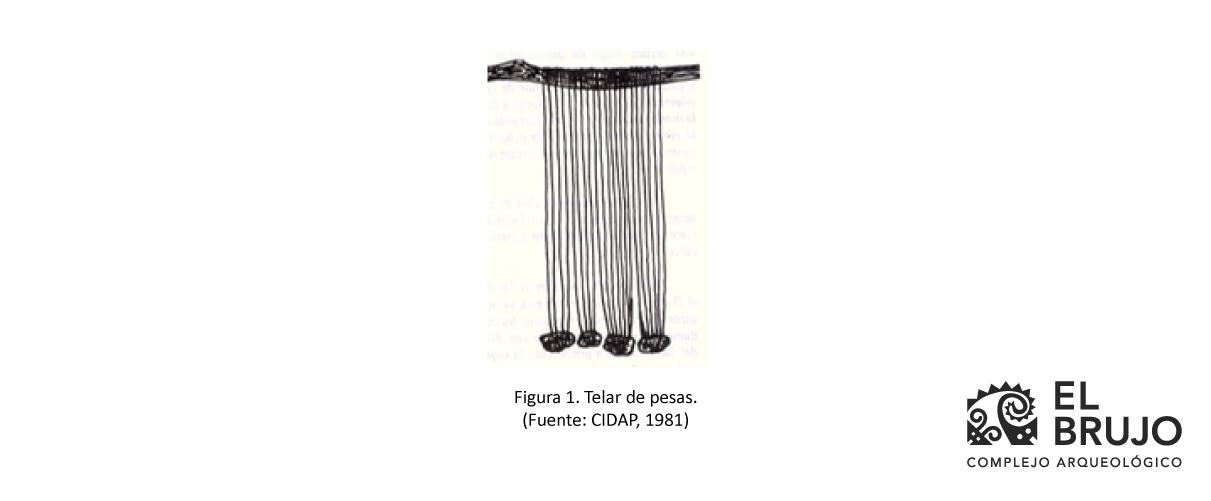

The loom is an instrument composed of one or more elements arranged to keep the warp threads taut. Early looms used tree branches to hold threads and tighten them by placing weights (see figure 1). Over the years, the structure was adapted depending on the desired fabric, among other considerations. We have records of two types of looms: horizontal and vertical ones.

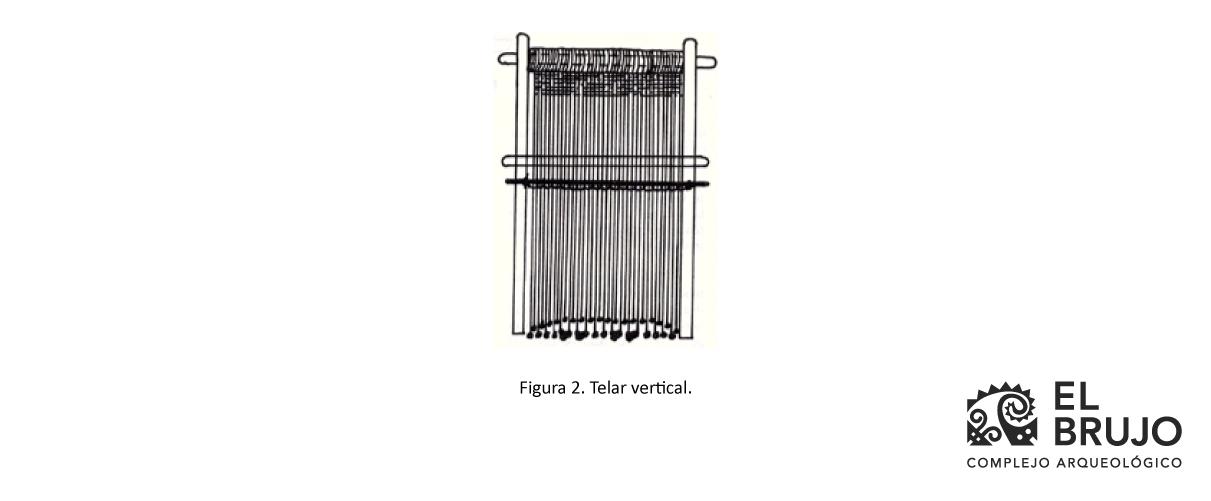

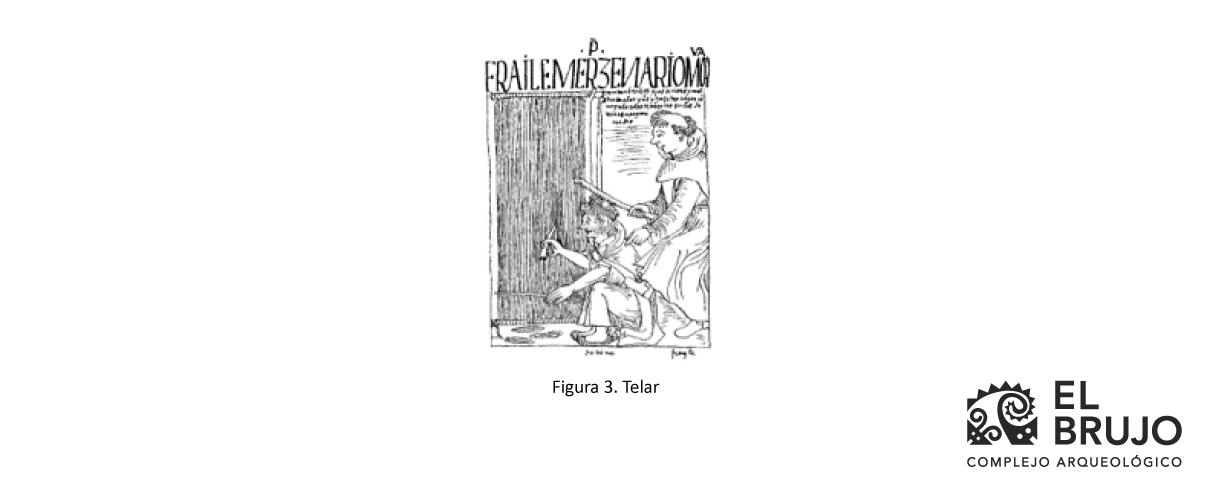

Vertical looms

Evidence of their use has been found in Egypt, Greece, Scandinavia and North America, among other places. This loom is made up of two fixed pieces of wood arranged horizontally and supported by two poles. In some cases, only one horizontal beam is placed at the top, and at the bottom the threads are tensioned with stone weights (see figures 2 and 3). The weaving is done from the top to the bottom (Muskus de Ovalle, 1981).

Horizontal looms

Depending on the way tension is exerted on the warp threads, we have two types of horizontal looms: backstrap loom and four-stake loom.

Backstrap loom

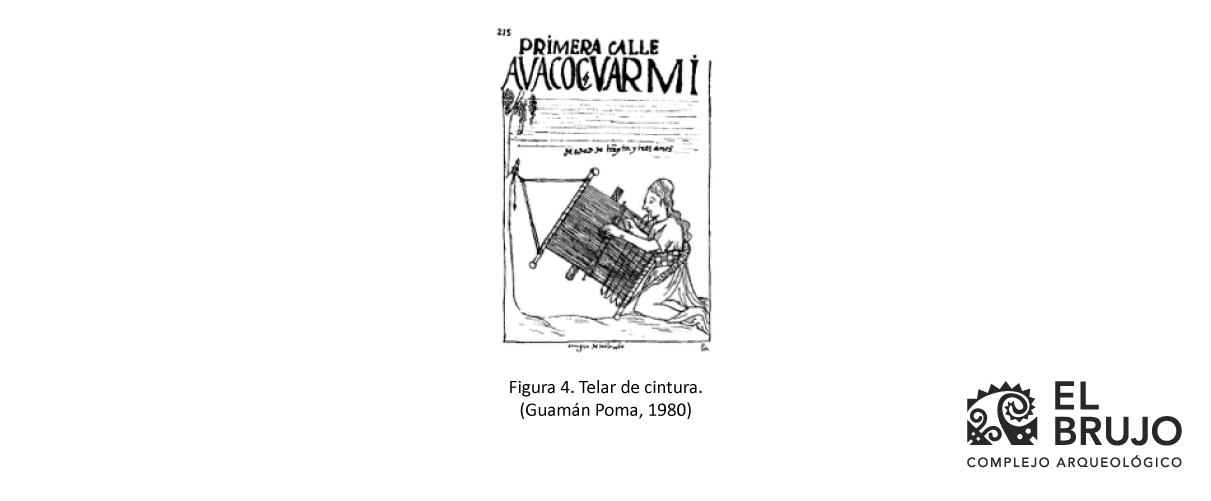

This type of loom is used nowadays in different countries, such as Mexico, Peru, Guatemala, Ecuador and Bolivia, among others. It consists of two wooden beams arranged horizontally at the top and bottom ends. The upper beam is tied to a fixed point, such as a tree trunk or a stake, and at the opposite end it is tied with a band to the weaver's waist (see figure 4). It is a lightweight loom and is used to make different complex structures (Awaspan, 2006).

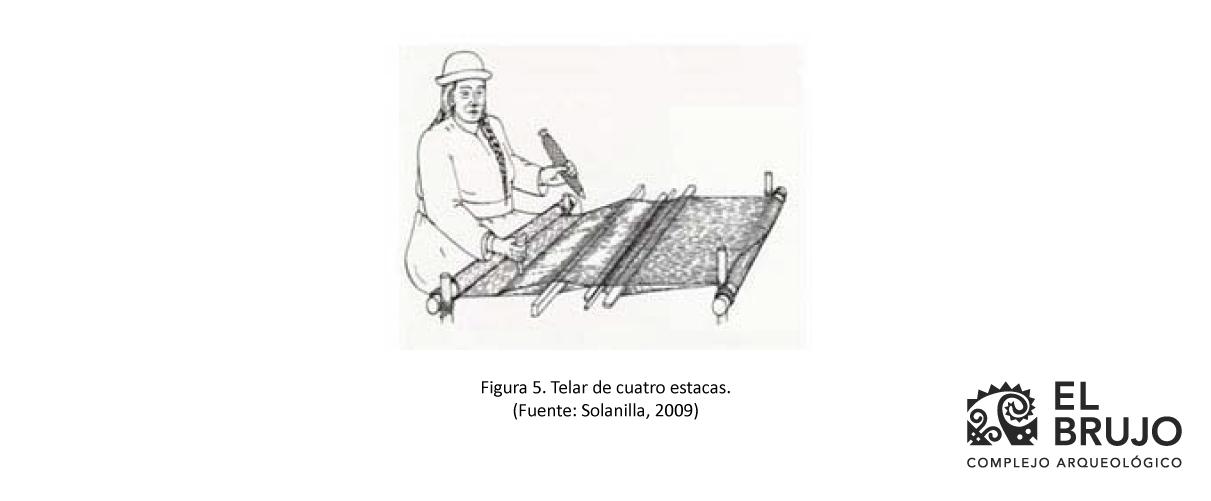

Four-stake loom

This loom is composed of two wooden beams placed parallel to each other and fastened close to the ground, tied to four stakes (see figure 5). The warp threads are arranged between the wooden beams, and the length of the warp will depend on the distance between the two pieces of wood placed (Solanilla, 2009).

With the arrival of the Spaniards, a new loom was introduced, the pedal loom, which was eventually incorporated into those mentioned above (Cultura, 2016).

We have relied on information found in Peruvian archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence of the looms. However, it is important to mention that there are more varieties of looms, such as the tripod loom used by the natives of Africa.

Instruments for weaving on the loom

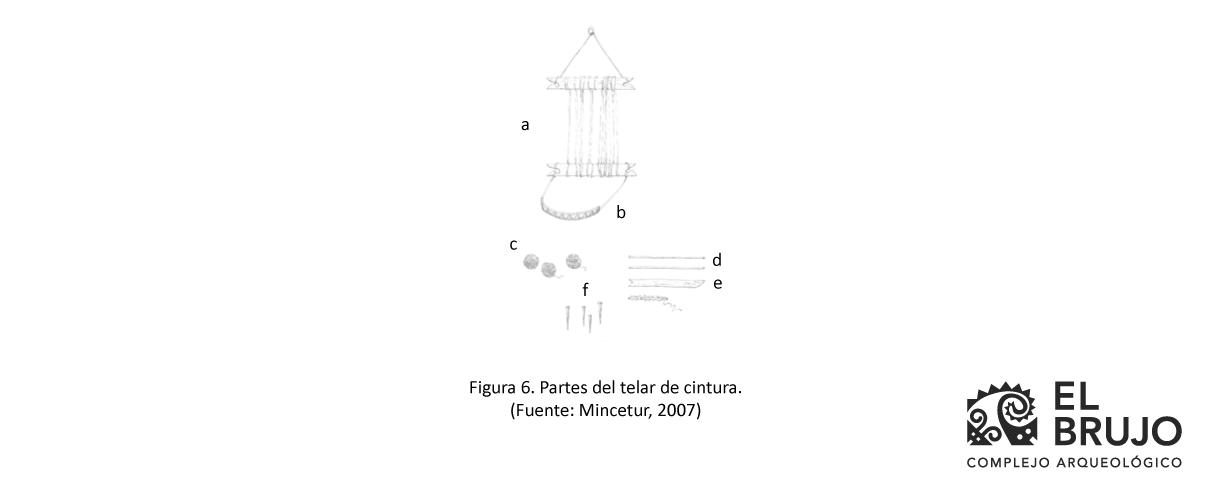

Most of the looms mentioned above employ instruments that perform the same function (Mincetur, 2007).

A: It is the tensioned structure of warp threads between two wooden poles, called loom or cungalpo.

B: It is the girdle or belt used by the weaver to tension the threads, called "belt", "loader" or "siquicha."

C: These are the skeins of wool.

D: It is a fragment of reed that is attached to the separating thread, called nail.

E: It is a fragment of reed or wood used to adjust the weft, known as a "sword", "calhua" or "quide."

F: These are stakes used on other types of looms.

These instruments are necessary to make a fabric, although they are not the only elements that are part of the loom.

A conversation about the backstrap loom

As we have been able to see, the loom technique is a practice that comes from pre-Hispanic times and, over the years, has been adapted to different societies up to the present. Nowadays, this technique is being forgotten little by little, and, thinking about promoting its dissemination and knowledge, we interviewed a textile artisan with 19 years of experience in this work, Ms. Diana Silva.

How did you learn to weave on a backstrap loom?

DS. When I was a child, I used to live in Molino Cajanleque, and when I was 13 we moved to Farias. At that age, I wasn't very much interested in handicrafts or knitting, but my mother was always involved in knitting, whether with crochet, knitting pin or loom, since her childhood. I grew up watching her knit. My interest came about when I had my children, as I wanted to knit something for them. With that experience, I continued to practice knitting.

Then I got involved with some neighbors and friends from the community to attend fairs, such as the patron saint festival of the district of Chocope. We started to train with the support of different institutions, and we saw that we could generate income by selling woven products. Tourists also showed a greater interest in the fabrics made on the loom. My mother knew how to weave on a backstrap loom, and she taught a group of ladies who came from different places like Chota, Cajamarca.

Being a textile artisan, how do you think it has affected your life?

DS: We saw the possibility of working on something we liked, and in these years of intense work, we have become well-known. Nowadays we can compete on pricing. When we started, the women depended on their husbands, but thanks to this work, they feel more confident, with greater self-esteem and motivated to grow, organize and train themselves. Also, their husbands used to regard coming to the workshop as a waste of time, but when they began to see that we could generate income and that now we can contribute to the household and improve our quality of life, they recognized our work.

From your experience, why do you think textile craftsmanship is not practiced more often?

DS. Aside from being our cultural heritage, it is a job. We apply techniques that come from the sierra and that require time to be carried out. For example, it takes a week to make a bag with one of these techniques, without considering the materials needed to make it, and the artisans also perform other tasks, such as motherhood. Imagine the price it should have if we consider the daily work of the artisan. This has led to the loss of several good artisans. We are constantly competing with the low value given to textile products, which is the main reason for the lack of practice in this work.

Final Thoughts

As we have seen, textile practice in Peru has a long history as an economic, social, and religious activity, so it is not surprising that it is still practiced today. However, it is valid to ask ourselves how much longer we will be able to continue admiring and learning from these ancient practices. Considering the conversation that we had with Ms. Diana, artisanal work does not receive the recognition and value that it deserves from society, which leads artisans to stop performing their trade. In addition to the above, we should also mention that this is not the only traditional expression in danger of disappearing. Vis-à-vis this situation, the question would be: what can we do to prevent it? A first step is to be aware of the history in its different forms behind each handicraft work and to give proper recognition to the workforce and the knowledge passed down from generation to generation.

Bibliography

- Awaspan, N. (2006). The art of weaving in the pre-Columbian Andes. In Awakhuni: Weaving the Andean History (pp. 10-21).

- Bastiand Atto, M. S. (2000). Pre-Hispanic Textile Production. Social Research, 124 - 144.

- Bubba, C. (2013). Andean fabrics, the passion of Elayne Zorn (1952-2010). Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena, 201-217.

- Buitrón, D. (2000). Paracas fabrics, an expression of the technological and artistic knowledge of a regional society of ancient Peru. Bulletin of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- Carmona, G. (2006). Characterization of the Inca textile garments present in late archaeological sites in the extreme north of Chile. Chile.

- Cultura, M. d. (February 2016). Weaving our history. Our history and territory intertwined through textile-making. Lima.

- Manrique, E. (1999). Millenary fabrics from Peru. Lima: AFP Integra.

- Mincetur. (2007). Learning Manual: Handicraft profession. Backstrap loom.

- Muskus de Ovalle, C. (1981). The loom. Bulletin of the Inter-American Center for Handicrafts and Popular Arts, 2-6.

- Poma, G. (1980). New Chronicle and Good Government.

- Quevedo, Z. (2015). The revitalization of backstrap loom weaving in the Lambayeque region. Peru.

- Solanilla, V. (2009). The role of pre-Columbian weavers through sources and images. 18.

Researchers , outstanding news