- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Series on Andean food: The cuy (Guinea pig)

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

Magdalena de Cao to Once Again Host an International Mural Art Gathering ...

Explore El Brujo Through Virtual Tours: Culture and History at a Click ...

To receive new news.

By: Mary Avila Peltroche y Jose Ismael Alva Ch.

By Mary Avila Peltroche and Jose Ismael Alva Ch.

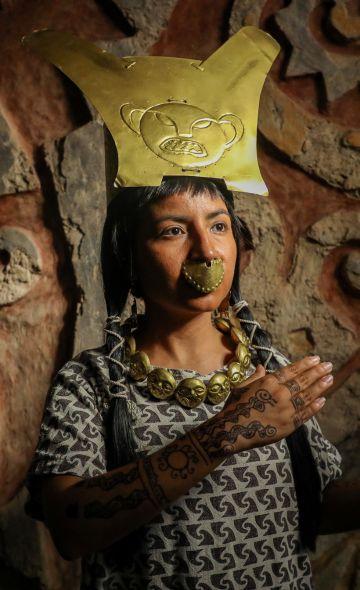

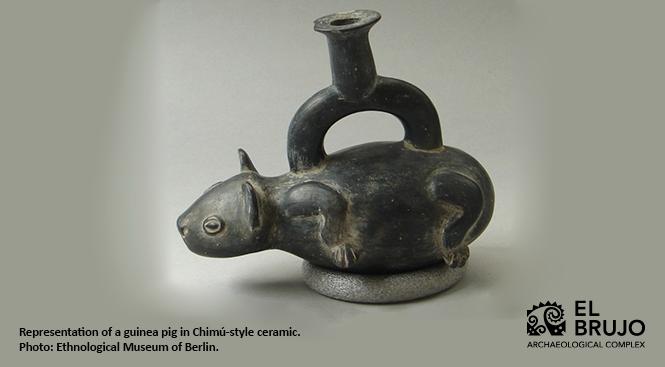

Guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) have been a main ingredient in Andean gastronomy. These animals have a long tradition that comes from ancient Peru, given that it has not only been used as food, but also as an animal for healing and divination purposes. Join us to learn about the history of the guinea pig, its nutritional properties and the customs associated with this popular rodent.

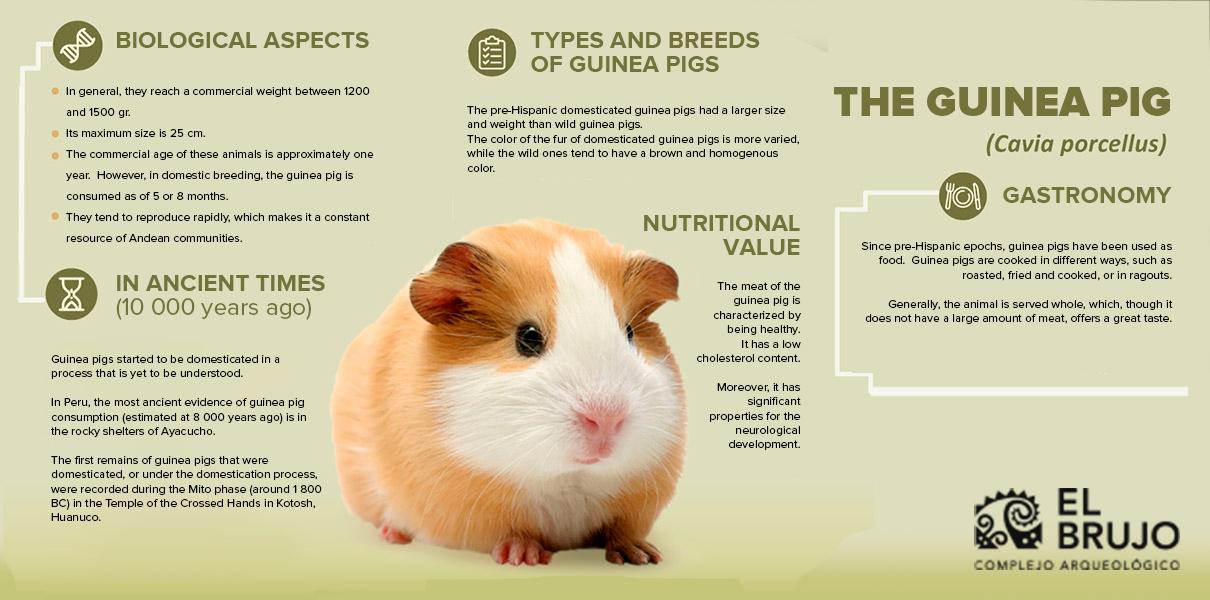

Some biological aspects of the guinea pig

Size and weight

Guinea pigs, in general, reach a commercial weight between 1200 to 1500 grams (4 months of age), although the weight of their commercialization starts at 750 grams to 850 grams, this being approximately between 9 to 10 weeks of age (Solari, 2010). Its maximum size is 25 cm in the case of improved guinea pigs, being smaller in the case of native guinea pigs, which reach an average weight of about 1000 gr.

Breeding cycle

These animals, like most rodents, tend to reproduce rapidly, which makes them a constant resource for Andean communities. The females usually go into heat between the first and second month of life; however, it is preferable that the crossing occur with males of two to three months of age and weighing 400-650 gr, which begin to be fertile at one month of age. The gestation time of these animals is 59-72 days (Avilés, D. et al, 2014).

Age of consumption

The commercial age of these animals is approximately one year, where there is a balance between the weight and the quality of the meat (Solari, 2010). However, in the case of domestic rearing, the guinea pig is consumed after 5-8 months for preparations such as fried, chactado (squashed under stones before frying) or in locro (a hearty thick squash stew); while younger animals, between 2-4 months, are used in soups that are believed to help cure respiratory diseases.

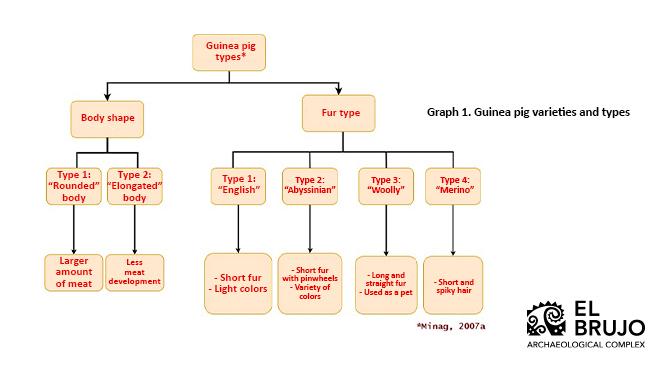

Types and breeds of guinea pigs

Currently, there are different types of guinea pigs, based on their physical characteristics:

"The Indians eat this animal with the skin, peeling it only as if it were a piglet, and for them it is a very delicious food ..." - Bernabé Cobo, 1653

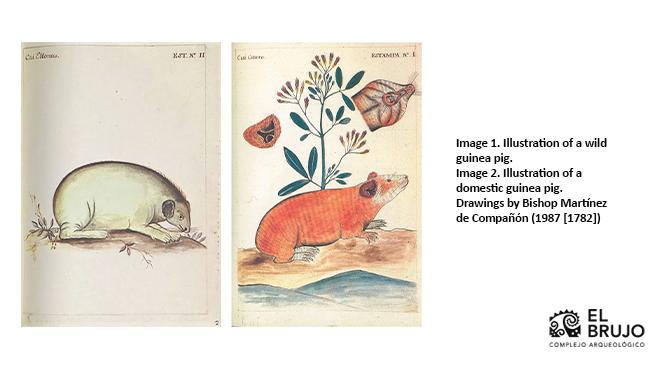

The variety of breeds of guinea pigs during pre-Hispanic times is not clear; however, the mummified specimens show that domestic guinea pigs were larger and heavier in contrast to wild guinea pigs. In addition, domestic guinea pigs had a greater variety of coat color, while wild guinea pigs tend to have a brown and homogeneous coat (Sandweiss & Wing, 1997).

Cuy: Domestication and archaeological evidence

Guinea pig remains are not abundant in archaeological contexts if we compare them with the bones of other animals such as llamas and alpacas. However, this does not mean that guinea pigs were not important in the diet of the ancient Andean settlers, but, rather, that the fragility of their bones means that they are easily destroyed by domestic animals such as dogs or other carrion animals (Valdez, 2000). Despite this, current research agrees that guinea pigs began to be domesticated approximately 10 000 years ago, in a process that we are still seeking to understand.

In Peru, the oldest evidence of guinea pig consumption is in the rocky shelters of Ayacucho. Around 8000 BC, the ancient Andean populations caught these animals by means of traps and kept them locked in boxes (León 2013: 322). It is during the Myth phase (around 1800 BC) in the Temple of the Crossed Hands in Kotosh, Huánuco, where we found remains of domesticated guinea pigs or in the process of domestication (Wing, 1972). These animals could have come from various types of wild guinea pigs, depending on the geographical area, probably from the Cavia aperea (Rodd, 1972) or Cavia tschudii (Wing, 1986; Walker, L. I. et al, 2014), as these are, genetically, the closest species.

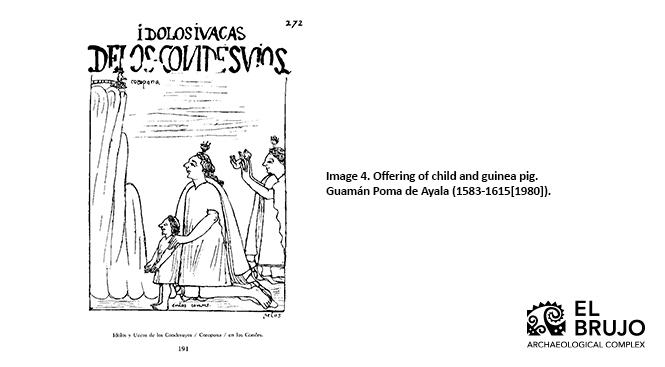

The customs and multiple uses of guinea pigs

Since pre-Hispanic times, these animals have been used as food. Guinea pigs were prepared in different ways: roasted, fried and cooked or in stews. In general, the whole animal is served, which, although it does not have a large amount of meat, has a great flavor.

In general, guinea pigs are usually raised in small pens in order to group the animals, separating the males from the females, except during the time of heat, where a male is usually placed in a cage with several females. According to Bernabé Cobo (1964 [1653]) these animals were raised inside the houses, a situation that can still be seen in Andean communities, where it is common to see these guinea pig pens inside the kitchens, or even to see these animals freely circulating around said spaces and taking advantage of waste from food preparation as part of their diet.

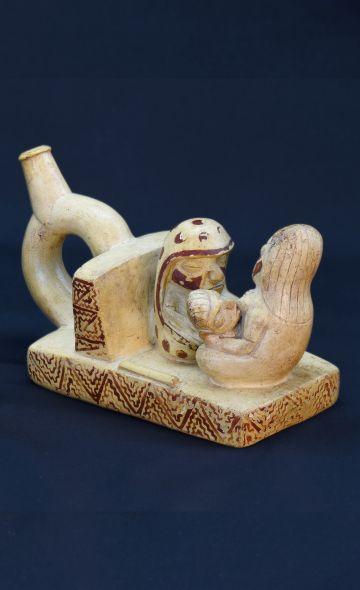

There is also evidence of its use for medicinal and divination purposes, as well as its use as sacrifice animals. According to Cobo (1964 [1653]) certain parts of the guinea pigs were used to calm some ills such as muscle injuries and ear infections. Furthermore, there is evidence within the archaeological record of the use of these animals for the purposes mentioned by Cobo, such as the case of the guinea pigs from the Lo Demás site, in the Chincha valley (Sandweiss & Wing, 1997). Likewise, nowadays guinea pigs are used by folk healers to diagnose illnesses and to heal those affected.

The introduction of guinea pigs into other continents has triggered their popularity as pets. Hence, in Europe and Asia it is common for them to be considered as pets and not as animals to be consumed as food or for healing purposes.

The guinea pig and gastronomy

The presentation of dishes made based on guinea pig is varied. It is a main ingredient in the picanterías (spicy food restaurants) of the southern highlands of Peru, and it also has an important presence in the gastronomy of countries such as Ecuador, Colombia and Bolivia. The guinea pig is also often served at special events such as weddings, negotiations, and other social events.

Modes of preparation

The guinea pig is usually prepared in different ways, the best known being Picante de cuy (spicy guinea pig), Cuy chactado (fried after being squashed under stones) and Cuy frito (fried guinea pig). In the town of Magdalena de Cao, guinea pigs are usually cooked as an Ajiaco (stew). In the case of Ajiaco, the animal is macerated the day before in pepper, salt, garlic and vinegar. After maceration, it is parboiled before being fried. The other type of preparation is the stew, where oregano, salt, pepper and chicha de jora (germinated corn beer) are added. Then the onion, oregano and ají panca (Peruvian red pepper) are browned, and the Guinea pig pieces are put to fry. Finally, it is served with rice, potato and Creole salsa.

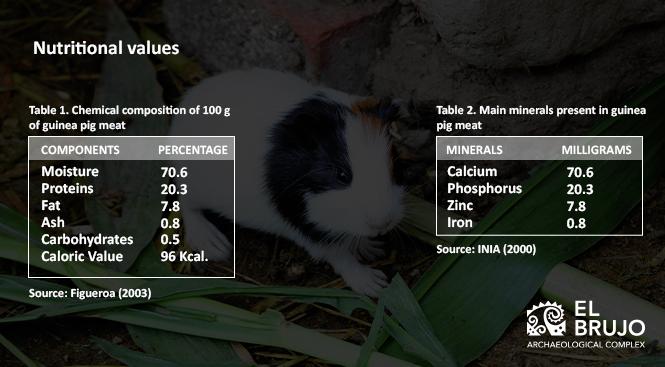

Nutritional value

The guinea pig is characterized by being a healthy meat, highly digestible, low in sodium and by having low cholesterol content. In addition, it is an important source of Vitamin B and linoleic and linolenic fatty acids, important for neurological development.

When it comes to this animal, the utilization concerns mainly its meat (65%), the rest being represented by the use of viscera (26.5%), hair (5.5%) and blood (3%) (Avilés et al, 2014).

Final notes

From their domestication to their adoption as pets, guinea pigs have played an important role in social relationships. Their nutritional value made them a culinary delicacy showing a great tradition in the Andean territory to this day. Although home-breeding of guinea pigs is decreasing more and more, the production lines have chosen to turn this resource into one of the main ones for local consumption and export. And, although this gives guinea pigs a privileged place in trade, it is important to remember that, if it had not been for those communities that kept this long tradition alive, we would not have in it a resource that is so precious and which must be valued more and more every day.

Cited references

Avilés, D. F., Martínez, A. M., Landi, V., & Delgado, J. V. (2014). The guinea pig (Cavia porcellus): an Andean resource of interest as an agricultural food source. Animal Genetic Resources / Resources génétiques animales / Recursos genéticos animales, 55, 87-91.

Cobo, B (1964 [1653]) History of the New World. First part. Library of Spanish Authors. Volume XCI. Madrid: Atlas editions

de Ayala, F. G. P. (1980). New Chronicle and Good Government (Vol. 1). Ayacucho Library Foundation.

Figueroa, F. (2003). The guinea pig, its breeding and exploitation; productive activities. Newsletter edited by IDNA.

INIA (2007) Facing urban poverty through agriculture - East Lima case - Peru. http://repositorio.inia.gob.pe/handle/inia/337

León Canales, E. (2013). 14,000 years of food in Peru. Fondo Editorial Universidad de la Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Lima.

Martínez Compañón, B. J. (1987 [1782–85]). Trujillo del Peru, Volume VI, Fournier, Madrid.

PERU. Ministry of agriculture. 2007a. Strategic plan for the guinea pig production chain. Cavia porcellus. http://www.minag.gob.pe/dgpa1/ARCHIVOS/PE_Elaboracion_cuy.pdf

Rood, J. P. (1972). Ecological and behavioral comparisons of three genera of Argentine cavies. Anim. Behav. Monogr. 5, 1–83.

Solari G. (2010) Guinea Pig Breeding Technical Data Sheet. Practical Solutions-ITDG. Lima Peru.

Sandweiss, D. H., & Wing, E. S. (1997). Ritual rodents: the guinea pigs of Chincha, Peru. Journal of Field Archeology, 24 (1), 47-58.

Valdez, L. M. (2000). Approaches to the study of the guinea pig in ancient Peru. Bulletin of the Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, 3 (3), 16-19.

Walker, L. I., Soto, M. A., & Spotorno, A. E. (2014). Similarities and differences among the chromosomes of the wild guinea pig Cavia tschudii and the domestic guinea pig Cavia porcellus (Rodentia, Caviidae). Comparative cytogenetics, 8 (2), 153–167.

Wing, E. S. (1972). Utilization of animal resources in the Peruvian Andes. Andes, 4, 327-351.

Wing, E. S. (1986). Domestication of Andean mammals. High altitude tropical biogeography, 246-264.

Researchers , outstanding news