- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- First Archaeological Reconnaissance at El Brujo: The visit by Antonio Raimondi in 1868

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Jose Alva y Augusto Bazán

One of the most fascinating topics about the El Brujo Archaeological Complex is precisely its name. According to the RAE (Royal Spanish Academy), a sorcerer (Brujo, in Spanish) is "that person who performs acts of magic or sorcery to dominate the will of people or modify events, especially if it causes a harmful or maleficent influence on people or their destiny."

Many stories and versions have been woven about the origin of the name, the most accepted being the fact of the representative number of shamans in the current town of Magdalena de Cao. It is also assumed that prominent teachers would have preferred the great court of the Huaca El Brujo or Huaca Cortada to perform their rituals.

However, this article does not pretend to understand the reason for the name but, rather, its antiquity, and who, for the first time, registered it, making the first efforts to identify the many edifices and spaces that make up the archaeological complex today.

Antonio Raimondi was an Italian naturalist who immigrated to Peru in 1850 (Figure 1). He soon stood out by assuming the chair of Natural History, taught at the Royal College of Medicine of San Fernando, and participating in scientific expeditions to evaluate the guano deposits in the Chincha Islands and the saltpeter deposits in Tarapacá [1].

The outstanding performance of Raimondi in these works was vital for the Peruvian State to finance its exploration projects and systematic recognition of the country's natural resources, an ambitious undertaking for the time.

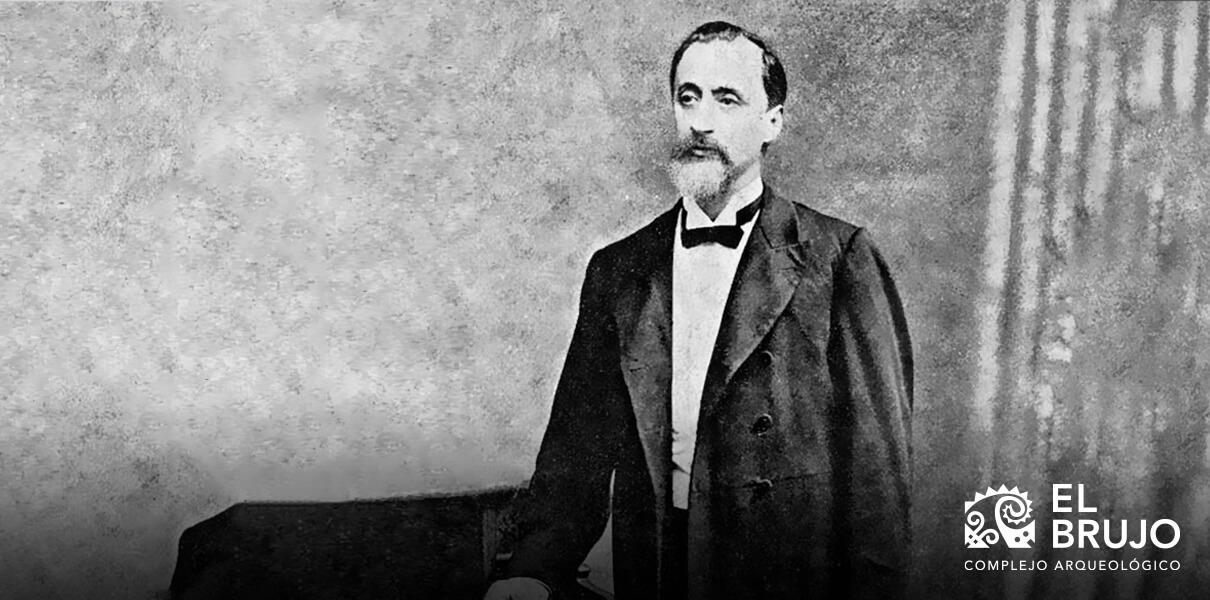

In this context, on the afternoon of May 20, 1868, Antonio Raimondi arrived in the town of Magdalena de Cao and stayed there for four days as a base for his visits to the different places in the lower valley of the Chicama. As was his custom, he wrote his observations in notebooks that have recently been published in a digital version by the National Archive of the Nation (Figure 2).

Pages 32 and 33 of A. Raimondi's notebook, where you can read his notes and a sketch of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex. Image: General Archive of the Nation.

Pages 32 and 33 of A. Raimondi's notebook, where you can read his notes and a sketch of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex. Image: General Archive of the Nation.

The following day, during his tour of the Chicama countryside, the naturalist paid attention to a series of pre-Hispanic edifices of medium height located in front of the coast. The density of these huacas led him to suppose that this area of the valley, provided with numerous lagoons with fish, housed a considerable population in ancient times.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the name El Brujo made reference to the entire cove located to the west of the current archaeological complex. This beach was, as in the present, frequently crowded during the summer months by the inhabitants of Magdalena de Cao and the nearby farms.

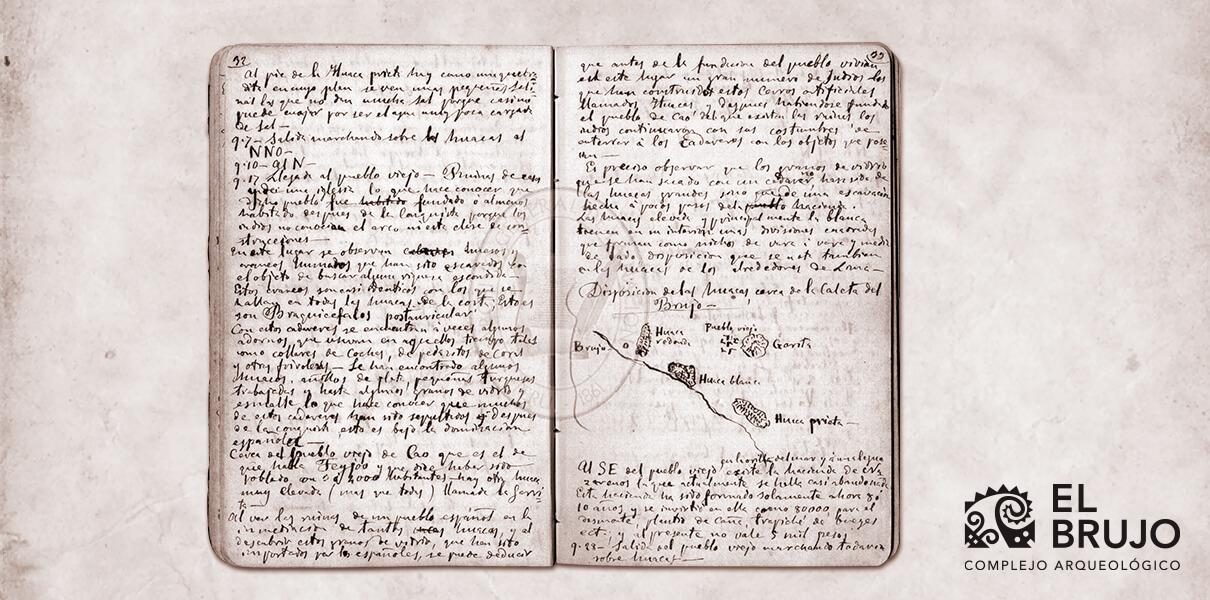

Raimondi was not able to specify the origin of the El Brujo denomination in the area. However, he recorded the names that were used at that time to designate the most representative mounds of the archaeological complex. Huaca Redonda was the northernmost building of the pre-Hispanic settlement and, although its shape was not strictly related to the name, it was remarkable in height. Considering the direction of the displacement and the sketch made by the naturalist, Huaca Redonda does not seem to be anything other than the current Huaca Cortada.

(Figure 4). Despite this, it is striking that Raimondi, being a diligent observer, had not dedicated any description of the notorious cuts made by looters on the southern front of Huaca Cortada, which leads to the assumption that the gigantic cuts of said building were made in times after his visit to the complex.

Current view of the Huaca Cortada (or El Brujo), identified as Huaca Redonda by Antonio Raimondi.

Current view of the Huaca Cortada (or El Brujo), identified as Huaca Redonda by Antonio Raimondi.

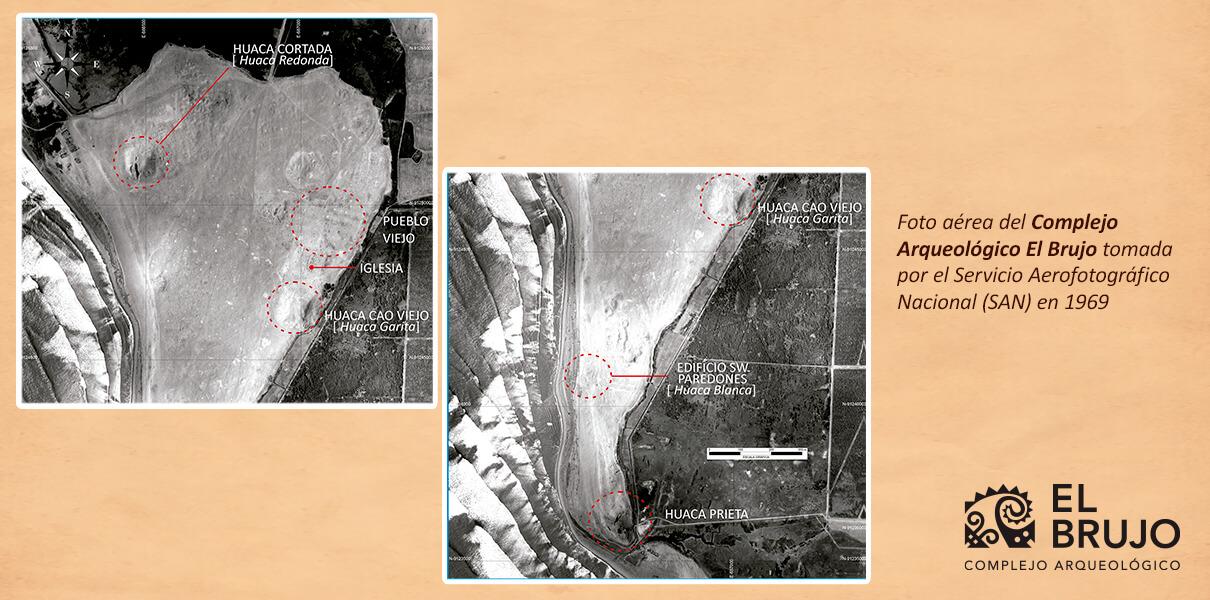

The Huaca Blanca is located on the beach line. It was about 10 yards high (8.4 meters approximately) and was built with small adobes. The upper part of the huaca had a series of quadrangular divisions from 1 yard to 1 and a half yards (84 cm to 125 cm, approximately). The fact that a section of this huaca was destroyed by the ocean waves, and understanding that the ancient Peruvians were diligent in choosing their settlements, led Raimondi to suppose that in remote times the sea had a greater recess than that existing in the 19th century. The description of Huaca Blanca is congruent with the southwest edifice of the Paredones sector, which shows a profile of adobes massively organized in groups, commonly referred to as BAT (interlocking adobe blocks). This technique has been reported and widely documented in the Moche buildings of the complex and the region.

Of Huaca Prieta, located at the southern end of the complex, little was said. Raimondi points out that it was built of boulders and earth, giving it the appearance of a natural mound. On the other hand, he details that at the base of Huaca Prieta there were small salt deposits, probably formed by the mixture of seawater and groundwater.

Heading north, Raimondi reached the so-called Old Town, which was made up of the “ruins of houses and a church” [1]. The surface of the place showed the traces of centuries of looting. The Italian explorer detailed the existence of numerous bones and skulls with characteristics similar to those that he had seen in indigenous cemeteries along the Peruvian coast. These human remains still conserved the remains of their grave goods, comprising ceramic vessels, silver rings, shell necklaces and small objects made of turquoise and glass. All these elements allowed Raimondi to deduce that this town must have been founded in times after the Spanish conquest and occupied by a large native population during the colony.

The last place that Raimondi visited is Huaca Garrita (or Garita), one of the highest mounds in the entire settlement. The sketch that depicts the layout of the old edifice at El Brujo shows that Huaca Garrita is adjacent to the Old Town. This undoubtedly reveals that said mound is the current Huaca Cao Viejo, the temple-like edifice with the largest archaeological interventions, where the funerary context of the Lady of Cao was found.

The documented visit of Antonio Raimondi to the El Brujo Archaeological Complex in the fall of 1868, constitutes a valuable precedent in the archaeological research process. It marks a milestone in the knowledge of the history of Magdalena de Cao and its customs, as well as the names by which the Chicama population called the huacas of El Brujo a century and a half ago (Figure 3).

Aerial photo of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex taken by the National Aerphotographic Service (SAN) in 1969. The names in capital letters are those used today, while those in square brackets are those recorded by Antonio Raimondi during his visit.

Aerial photo of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex taken by the National Aerphotographic Service (SAN) in 1969. The names in capital letters are those used today, while those in square brackets are those recorded by Antonio Raimondi during his visit.

To this we must add the first inferences related to the chronology of the occupation of the archaeological complex. Based on the mode of construction, the state of conservation of the architecture and the use of certain objects, Raimondi distinguishes a colonial era represented by the Old Town and another pre-Hispanic era represented by the great huacas.

Almost 80 years later, Junius Bird's archaeological excavations at the well-known Huaca Prieta would reveal that the pre-Hispanic occupation at El Brujo dates back at least 5 000 years before the present time.

[1] Lizárraga, Lizardo. 2003. "Raimondi and his links with European science, 1851-1890". Bulletin of the French Institute of Andean Studies 32 (3): 517-537.

[2] General Archive of The Nation. Republican Archive, Antonio Raimondi Fund, Trip to Trujillo. Chicama Valley - San Pedro de Guadalupe - Monsefú - Chiclayo - Lambayeque and Hacienda de Patapo (1868), Pp. 32.

Link to the General Archive of The Nation / Antonio Raimondi Fund:

http://200.37.79.140:8080/ConsultaWeb/showInformacionNodo/148fe7b4db476000000000000000007b

Link to the General Archive of The Nation / Antonio Raimodi Fund / Trip to Trujillo. Chicama Valley- San Pedro de Guadalupe- Monsefú- Chiclayo- Lambayeque and Hacienda de Patapo:

http://200.37.79.140:8080/ConsultaWeb/showImagenes/148ff19fc1513000000000000000007b/#inline_content

Researchers , outstanding news