- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The piruros of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex: Technology and tradition

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Katerine Albornoz

By Katerine Albornoz

INTRODUCTION

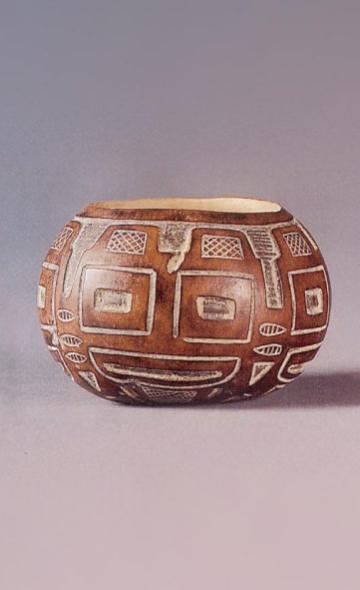

Textile making is one of the main activities developed by our ancestors. Textiles fulfill the function of protecting us from the environment and from climatic changes (Gayoso Rullier, 2007). Moreover, in its historical development, the manufacture of textiles acquired greater importance, since those of the best elaboration were considered as prestigious goods for political, economic and religious purposes, among others. In this way, the manufacture of textiles went through different stages of production and different tools were used in said process, such as spindles, weaving swords, needles and combs, among others. The collection of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex has a wide variety of these objects. In this note, we will talk about the piruro (a spindle counterweight), its archaeological evidences and its important function: the elaboration of threads (Figure 1).

PIRUROS IN THE PRE-HISPANIC WORLD

Research on textile production and its tools has been increasing. Next, we will make a brief account of the findings and research related to piruros carried out in the last 30 years.

Piruros have been the main means of yarn production in the pre-Hispanic world throughout the entire ancient Peruvian territory (Baitzel & Goldstein, 2018; Berrocal Flores, 2009; Cárdenas M & Hudtwalcker M., 1997; Mac Kay & Santa Cruz, 2000; Ponte, 2017). One of the main finds is the one made in the urban sector of the Huaca del Sol y de la Luna, in the Moche Valley, where more than 400 piruros made of clay, stone, copper and bone were found, linked to the production of cotton threads (Chapdelaine et al, 2001). To the south, at the ‘El Purgatorio’ archaeological site, in the Casma Valley, ceramic and stone piruros, associated with the dwelling, ceremonial and burial areas were recorded (Vogel et al, 2016).

On the south coast, in the Nazca Valley, on the sites of Huayuri (Siveroni & Tiballi, 2016) and Pataraya (James Edwards et al, 2008), evidence was recorded of textile production workshops where they found the final product (textiles), the production scraps and textile tools: piruros, spindles, swords, needles, etc.

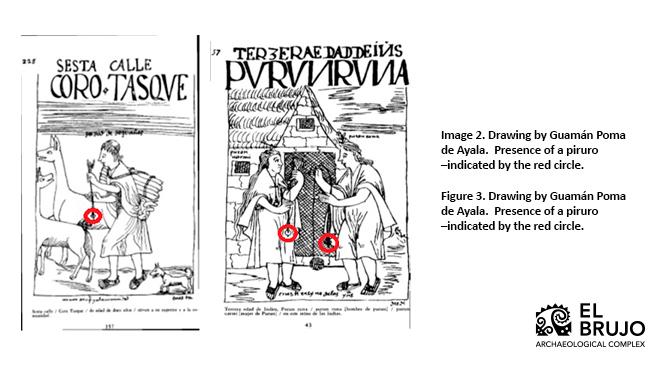

BETWEEN ETHNOHISTORY AND ETHNOGRAPHY

Few chroniclers mention the spinning process. One of these is Garcilaso De la Vega, (1976). In his work "Royal Commentaries" he refers to the spinning process, mentioning the presence of the spindle for spinning and that this trade was inherent to women. However, there is information that indicates that this task was not only carried out by women, but also by men. This can be seen portrayed in one of the drawings by Guaman Poma de Ayala (1980) in his work “New Chronicle and Good Government” (Figures 2 and 3).

There are some ethnographic references that can help us to better understand the spinning process and its implications. In the town of Molino, Argentina, the textile activity is carried out by both men and women, but in the spinning process they include only the women, who learn to spin and weave from a very young age with pieces of sheep's wool. It is only at the age of 12 that they aspire to use camelid threads (Teves, 2011).

How is the piruro used?

In the Andean communities of today, we can still observe the use of spindles and piruros for the elaboration of the threads. Cotton fibers or those made from animal hair, previously selected and cleaned, are stretched and partially twisted with the hands. The end of the strand is tied to the spindle, a stick with thin ends, which carried the piruro on its bottom end, which serves as a counterweight to facilitate the rotation of the spindle and the twisting of the thread (Franquemont et al, 1992; Solar D., 2017; Teves, 2011).

Regarding the cultural implications, Teves (2011) mentions that the female thread spinners feel that by making threads they are conveying a part of themselves. On the other hand, Prieto (2014) states that there is a relationship between the textile-making objects. The process of spinning or weaving has a symbolic charge related to an ancient deity of Lambayeque society.

PIRUROS AT EL BRUJO

The archaeological interventions carried out by Wiese Foundation at the El Brujo Archaeological Complex (CAEB) as of the 1990s have allowed us to discover a series of funerary contexts from the Cupisnique (800-500 AD), Moche (100- 800 AD), Transitional (800-900 AD), and Lambayeque (900-1200 AD) epochs, coming from the Paredones Sector and the different spaces of the Huaca Cao Viejo.

The CAEB collection of piruros is made up of 117 specimens, of which 4 are from the Cupisnique context, 2 from the Transitional context, 11 from the Mochica context, 22 from the Lambayeque context; while the remaining 76 piruros correspond to undefined contexts. However, from the formal decorative characteristics, it has been possible to distinguish that some of them corresponded to the Mochica (29) and Lambayeque (15) contexts.

The piruros have a variety of shapes ranging from biconic to spherical, frustoconical, disk-shaped, among others, in addition to having various decorations that may be related to the shape.

Next, we will present the most representative piruros of the collection.

PIRUROS FROM THE CUPISNIQUE EPOCH

The piruros found in the Paredones Sector are made of ceramics and stone, stone being the most common material. In the sample, there are different shapes, the most recurrent being the biconic. Two models have been chosen for this study. The first one is made of ceramic and presents a particular shape, called frustoconical, with incisions as a decoration on the body. Its height is 1.7 cm, its diameter is 0.4 cm and its weight is 5 gr (Figure 7). The second piruro is made of biconical stone, with incisions as decoration in the upper part. Its height is 1 cm, its diameter is 0.4 cm and its weight is 68.6 gr (Figure 8).

PIRUROS FROM THE MOCHICA EPOCH

The Mochica piruros found in the Upper Platform of the Huaca Cao Viejo are made of ceramic and are of different shapes. Among them, the most recurrent ones are the biconic and the spherical. We selected two piruros with particular characteristics. The first one (Figure 3) is made of stone, conical in shape with a convex base and inlaid with mother-of-pearl on the upper part as decoration. It is 1.1 cm tall, 0.4 cm in diameter and weighs 2.9 g. The next one (Figure 4) has a globular body with a conical end, with decorations in incisions. Its height is 1.8 cm, its diameter is 0.4 cm and its weight is 4 gr.

PIRUROS FROM THE LAMBAYEQUE EPOCH

The Lambayeque piruros found in the North Front of the Huaca Cao Viejo are made of ceramic, metal and stone, the former being the most recurrent material. In addition, they have a wide variety of shapes. Among them, the frequent ones are the spherical and the biconic shape. Two models have been chosen. The first one presents a biconic shape, with incisions as decoration on the upper part. Its height is 1.9 cm, with a diameter of 0.5 cm and a weight of 6.2 g (Figure 5). The second piruro has an unusual shape: it is a disk. It has an internal diameter of 1 cm and an external diameter of 4.2 cm, with a weight of 22 gr (Figure 6).

THREAD SPINNING: A MILLENNIAL TRADITION

Within textile making, the elaboration of the threads is one of the main specialized works carried out in the pre-Hispanic world and which lasts to this day among the Andean communities. This work began after the selection, cleaning and processing of the raw material (cotton or wool). The spinning can be divided into two parts, the first one consists in transforming the fiber into yarn using the spindle as a support and the piruro as a flywheel in order to drive the spindle at the moment of rotation and provide greater speed; in the second part, two threads are joined and twisted to prevent them from breaking (Almanza Lurita, 2020; Loughran-Delahunt, 1996).

The most recent research proposes that the piruros could have been used as a personal adornment or status symbol (Vogel et al, 2016) due to the decoration and shape that they have. On the other hand, it is possible that the designs are a way of indicating the thread-spinner’s belonging to a group through a personal mark (Marcus, 2016).

The sample of piruros from the CAEB includes specimens from the Formative period to later times and, therefore, we could say that thread-spinning through the use of spindles and piruros occurred in a prolonged and continuous manner. If we consider that these instruments are still in use today, we can say that their use in history is more than 4800 years old.

Unfortunately, despite being an important piece in the manufacture of notable textile pieces, very little is known about the relationship that exists between the shape of the piruro and the quality of the thread, the dexterity and the level of textile production reached by the ancient inhabitants of the Complex. Investigations will continue in that sense and in other directions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Almanza Lurita, I. (2020). Development and application of Lean Manufacturing and innovation tools to improve the artisanal manufacturing process of alpaca fiber yarn in the alpaca communities of Peru. At Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Baitzel, S. I., & Goldstein, P. S. (2018). From whorl to cloth: An analysis of textile production in the Tiwanaku provinces. Journal of Anthropological Archeology, 49 (December 2017), 173-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2017.12.006

Berrocal Flores, S. (2009). Characterizing late pottery from the lower Negromayo River basin (Lucanas – Ayacucho): Preliminary contributions based on ceramics from the Canichi archaeological site. Archeology and Society, 20, 1-29.

Cárdenas M, M., & Hudtwalcker M., J. A. (1997). NOTES ON FUNERAL PRACTICES IN PUERTO SUPE, DEPT. OF LIMA, DURING THE MIDDLE HORIZON. Archeology Bulletin PUCP, 1, 233-239.

Chapdelaine, C., Millaire, J. F., & Kennedy, G. (2001). Compositional analysis and provenance study of spindle whorls from the Moche Site, North Coast of Peru. Journal of Archaeological Science, 28 (8), 795-806. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2000.0588

De la Vega, G. (1976). Royal Commentaries.

Franquemont, E. M., Franquemont, C., & Isbell, B. J. (1992). Awaq ñawin: The weaver's eye. The practice of culture in weaving. Andina Journal, 19 (1), 47-80.

Gayoso Rullier, L. H. (2007). WEAVING THE POWER. The textile specialists of Huacas del Sol y de la Luna. Universidad Pablo de Olavide.

Guaman Poma de Ayala, F. (1980). New Chronicle and Good Government.

James Edwards, M., Fernandini Parodi, F., & Alexandrino Ocaña, G. (2008). Decorated Spindle Whorls From Middle Horizon Pataraya. Ñawpa Pacha, 29 (1), 87-100. https://doi.org/10.1179/naw.2008.29.1.002

Loughran-Delahunt, I. (1996). A Functional Analysis of Northwest Coast Spindle Whorls [Western Washington University]. internal-pdf://loughran-delahunt-analysisisspindles-2497462530/Loughran-Delahunt-AnalysisisSpindles.pdf

Mac Kay, M., & Santa Cruz, R. (2000). The excavations of the Huaca 20 Archaeological Project (1999 and 2001). PUCP Archeology Bulletin, 0 (4), 583-595.

Marcus, J. (2016). Barcoding spindles and decorating whorls: How weavers marked their property at Cerro Azul, Peru. Ñawpa Pacha, 36 (1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00776297.2016.1169715

Ponte, V. (2017). Puna shepherds from the Middle Horizon period in Callejón de Huaylas, Peru. Archeology and Society, 0 (18), 95-130.

Prieto Burmester, G. (2014). Spinning and weaving tools in tombs and votive contexts. Lambayeque: Evidence from textile specialists or mythical symbolism of an unknown goddess? Lambayeque culture: in the context of the north coast of Peru. Proceedings of the second Colloquium on the Lambayeque culture, 517-546.

Siveroni, V., & Tiballi, A. (2016). Domestic textile production in the late pre-Hispanic occupation of the Nazca region (south coast of Peru): A view from Huayuri, Palpa. Domestic textile production in the Late Pre-Hispanic period of the Nazca area (south coast of Peru): A view. New world, new worlds, October, 1-36. https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.69901

Solar D., M. E. (2017). Textile art and cultural identity of the provinces of Canchis (Cuzco) and Melgar (Puno). In The memory of the fabric (First). http://artesaniatextil.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/MEMORIA-TEJIDO-PERU-PARTE-1.pdf

Teves, L. (2011). The Ethnographic Study of Textile Activity as a contribution to the Characterization of the Way of Life in the Town of Molinos and its area of influence (Province of Salta). Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

Vogel, M., Buhrow, K., & Cornish, C. (2016). Spindle Whorls from El Purgatorio, Peru, and Their Socioeconomic Implications. Latin American Antiquity, 27 (3), 414-429. https://doi.org/10.7183/1045-6635.27.3.414

Researchers , outstanding news