- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The evolution of the containers in Ancient Peru: from mate (gourd) to ceramic? (I)

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

Magdalena de Cao to Once Again Host an International Mural Art Gathering ...

Explore El Brujo Through Virtual Tours: Culture and History at a Click ...

To receive new news.

By: Carlos Alfredo Fuentes Romero

By Carlos Fuentes Romero

Traditionally, it is thought that, before the advent of ceramics in Peru, around the seventeenth century B.C., mates (gourds) were the main supply for the tableware of the Andean peoples. Bowls, bottles and spoons could be made from this legume that grew on any farm or edge of an irrigation canal until not long ago. Is it correct, then, to say that the introduction of ceramics into the Andean territory eliminated the use of mates? Well, not necessarily.

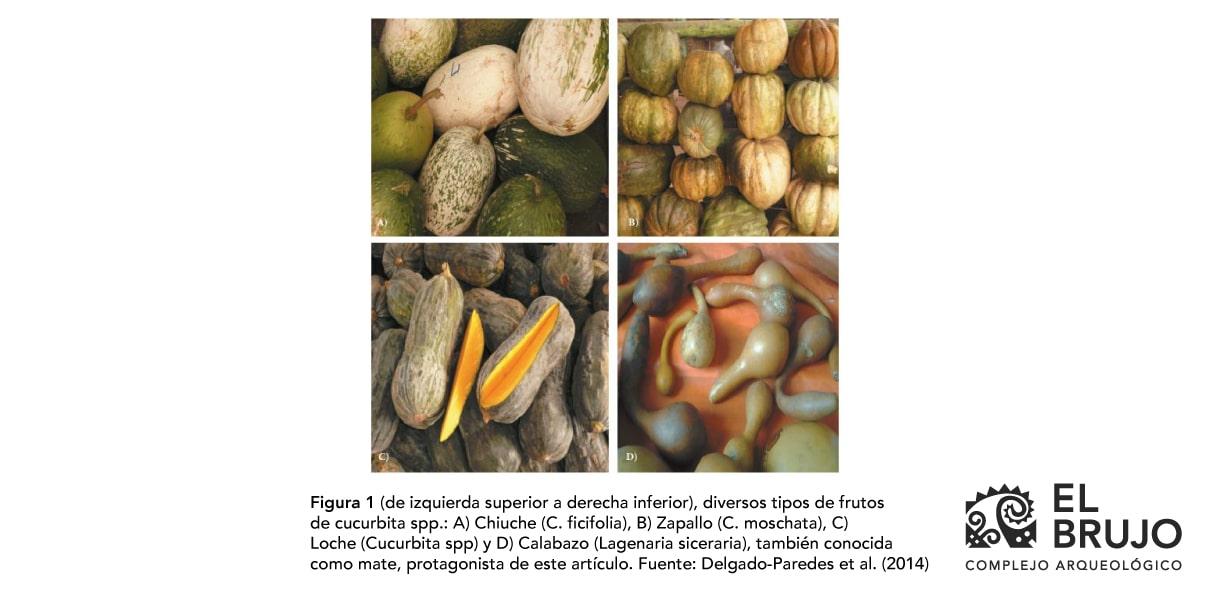

The mate (Lagenaria siceraria) is a plant element that has accompanied us for approximately 8,000 years (Vergara 2015); while ceramics only made their appearance in central Andean lands less than 4,000 years ago (Watanabe 2009). In this note, we will learn about the evolution of mate as a cultural object in Ancient Peru.

It is very likely that mate (L. siceraria) made its appearance in American lands already in a domesticated state; that is to say, this fruit may not have become a food native to America. In fact, it has been posited that their advent in this region was the result of the arrival of Asian populations that entered the Americas in the Holocene, as part of the well-known American Settlement, more than 15,000 years ago (Waters 2019). These populations, it is postulated, brought seeds from their place of origin after having obtained them as part of some contact that they had with the African continent, implying that this region was actually the one that saw the birth of the Lagenaria (Erickson et al. 2005). Aside from that, there are hypotheses that indicate that the arrival of these seeds was by means of the movement of sea currents (Zeder et al. 2006, Decker-Walters et al. 2004) and that at some point they were sighted by inhabitants of this region who were able to take advantage of them by cultivating them in these lands.

In Peru, the oldest evidence of mate in archaeological contexts is found in the caves of Tres Ventanas and Quiqché, located in the heights south of Lima, in the upper valley of Chilca, with an approximate antiquity of 7,000 B.C. (Engel 1970). Near the capital city of Lima is the Arenal complex, where evidence of mate dating back to approximately 6,000 B.C. was found, though it had already been domesticated by then (Cohen 1978).

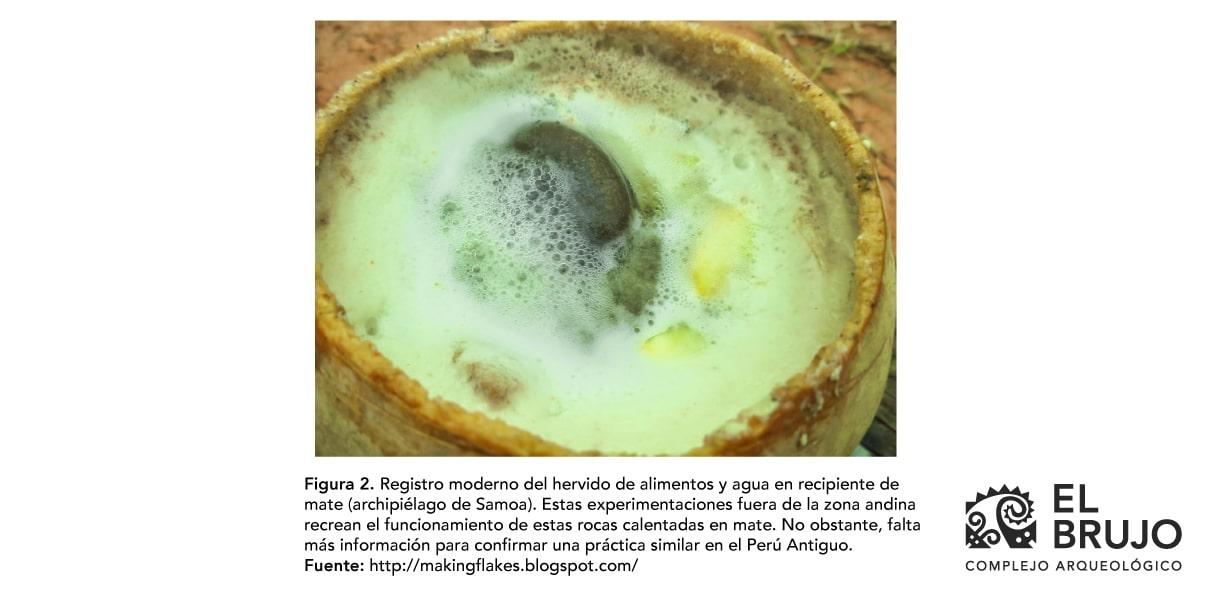

As for its functionality, mate has been largely used as a container, perhaps the first object with this functionality in the history of human beings (Bonavia 1991). Its fruit is opened to extract the seeds contained inside. The gourde is left to dry and, once hardened, it is used as a cup, plate or bottle (Ríos 2019). Its usefulness lies in storing and heating water, as well as serving food. This use is supported by a large amount of thermofractured stones found in many coastal archaeological sites. It is conjectured that these stones, very hot, were used to heat the added content inside the mates, whether solid or liquid (Vergara 2015, León 2013).

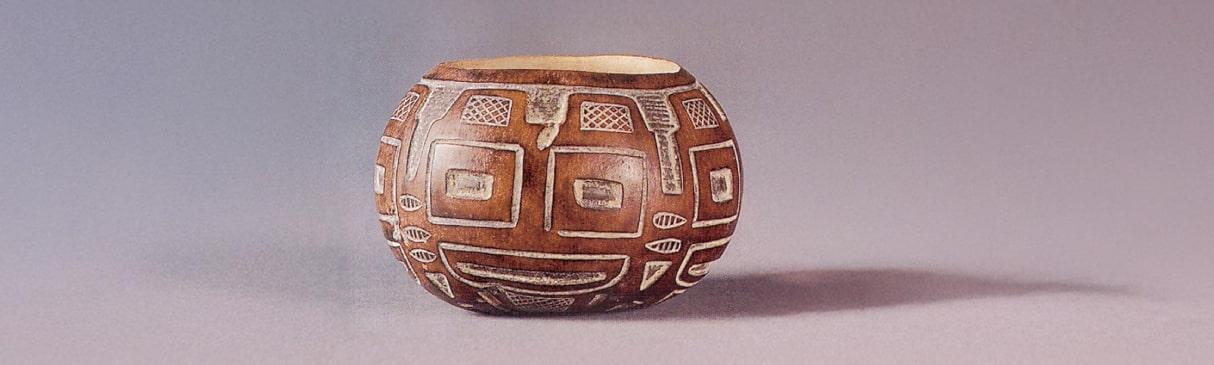

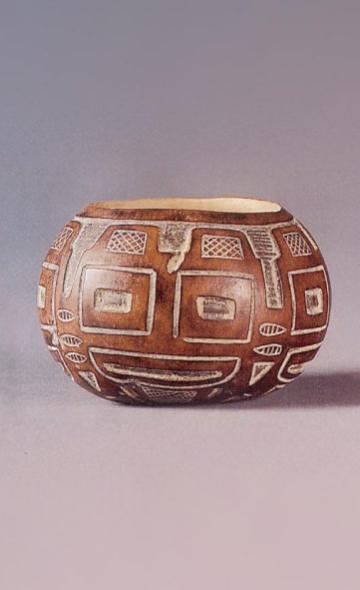

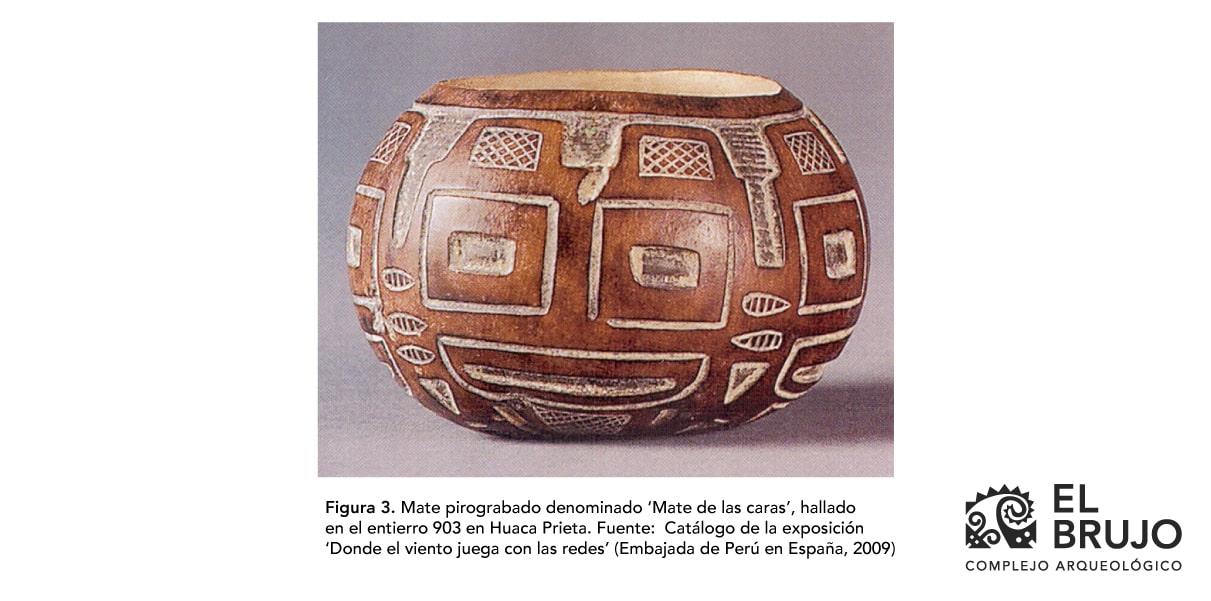

Its use responded to functional purposes of a domestic order and in rituals linked to mortuary contexts, as an offering. This characteristic has been evidenced in pyrographed mates. These mates are characterized by featuring designs made by using a sharp punch throughout the outer layer of the fruit. At the CAEB, we have a replica of a pyrographed mate found in burial 903 of Huaca Prieta (Bischof 1999). The discovery of this worked mate was part of the discoveries made by Junius Bird around 1946. This piece was part of a simple funerary context which would be at least 3,000 years old (Bird 1985).

The great protagonism of mate in the life of the settler of ancient Peru would begin to change around 1800 B.C., approximately, due to the advent of ceramics in this region (Manrique 2001). The discovery of this inorganic element brought about social changes with profound cultural consequences that we still witness today. That being said, we have observed that mate has been a fundamental organic element in Andean history, which was adapted to our needs. As we will see in a further installment, the advent of ceramics did not mean the end of its use.

What did you think of this first part? The second part of this story will be published shortly. Be attentive, because we will soon bring you news. Until next time!

References

Bird, J. (1985). The Preceramic Excavations at the Huaca Prieta Chicama Valley, Peru. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, 62(1)

Bischof, H. (1999). The Carved Mates of Huaca Prieta: Evidence of Valdivia Art in the Central Andean Archaic? Archaeology Bulletin from PUCP, 3, 85-119

Bonavia, D. (1991). Peru. Man and History. From the origins to the fifteenth century. EDUBANCO

Cohen, M. (1978). Archaeological plant remains from the central coast of Peru. Ñawpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology, 16, 23-50

Decker-Walters, D. et al. (2004). Discovery and genetic assessment of wild bottle gourd [Lagenaria Siceraria (Mol.) Standley; Cucurbitaceae] from Zimbabwe. Economic Botany, 58(4), 501-508

Delgado-Paredes, G. et al. (2014). Characterization of fruits and seeds of some cucurbits in northern Peru. Revista Filotecnia Mexicana, 37(1), 7-20

Engel, F. (1970). Exploration of the Chilca Canyon, Peru. Current Anthropology, 11(1), 55-58

Embassy of Peru in Spain (2009). Exhibition of the catalog 'Where the wind plays with the nets'.

Erickson, D. (2005). An Asian origin for a 10,000 year-old domesticated plant in the Americas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(51), 18315-18320

León, E. (2013). 14,000 years of food in Peru. USMP Editorial Fund.

Manrique, E. (2001). Guide for a study and treatment of pre-Columbian ceramics.

Ríos, S. (2019). Handicrafts of Peru. History, tradition and innovation.

Vergara, E. (2015). Math. Iconographic Corpus, pre-Hispanic Peru. First Edition

Watanabe, S. (2009). Kaolin pottery in the Cajamarca culture (northern sierra of Peru). The case of the Middle Cajamarca phase. Bulletin of the French Institute of Andean Studies, 38(2), 205-236

Waters, M. (2019). Late Pleistocene exploration and settlement of the Americas by modern humans. Science, 365, 138

Zeder, M. (2006). Documenting domestication. The intersection of genetics and archaeology. TRENDS in Genetics, 22(3), 139-155

Researchers , outstanding news