- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Clothing at El Brujo: footwear

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Traveling to Trujillo? Do not hesitate to consider a visit to El Brujo, just an hour away from this city ...

To receive new news.

Por:

By Yuriko Garcia Ortiz

Imagine walking barefoot in the desert, in the forests, in the prairies and in the snow-capped mountains. Human beings, since time immemorial, when they moved more than today through geographies wilder than today's, needed to cover what allowed them to walk: their feet.

The archaeological record suggests that the oldest evidence of footwear use in the world comes from the Middle Upper Paleolithic (Gravettian), approximately between 30,000 and 24,000 BP in France (Europe), Iraq, and Israel (Asia) (Trinkaus, 2005; Wilczyński et al., 2019)(i). In this way, facing the need to constantly protect oneself from the hostile environment and achieve greater mobility in the territory (Ledoux et al., 2021), the first footwear in the world began to be made and used (Volken, 2014).

Footwear in ancient Peru

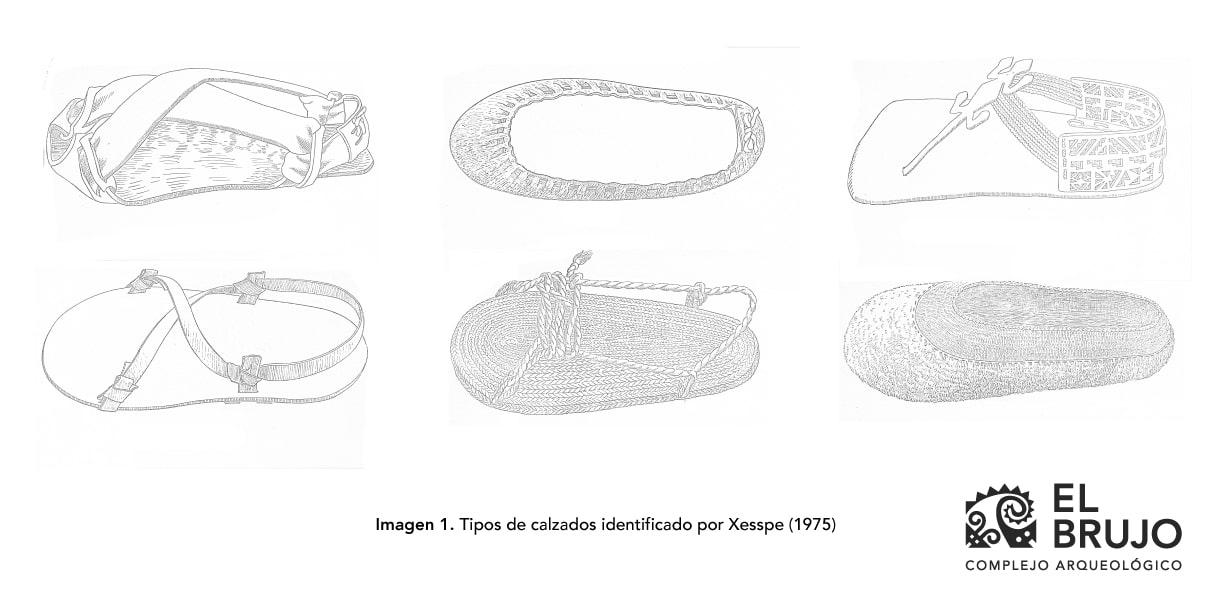

Research on archaeological footwear is considerably restricted due to the conditions of conservation of the pieces. The initial studies on footwear in ancient Peru were carried out by Mejía Xesspe (1975), based on the comparative analysis of various archaeological, historical and ethnographic sources. He sought to identify the origin of the different types used in the Andes, defining six: shukuy, seqoy, ushuta, chápito, llanke and pollqo.

The types identified by Mejía Xesspe came from the Late Horizon (1400-1532 A.D.) with the use of llankes (sturdy sandals) mainly in the Andes until the colony (1532-1821 A.D.) with the taxation of the "alpargateros" (espadrille makers) (Xesspe, 1975) and although the earliest data in pre-Hispanic Peru would be a pair of Paracas sandals (700 B.C.-200 A.D.) according to Meseldzic (1992), the use of footwear in periods earlier than approximately 500 B.C. is currently disputed, due to the absence of material evidence.

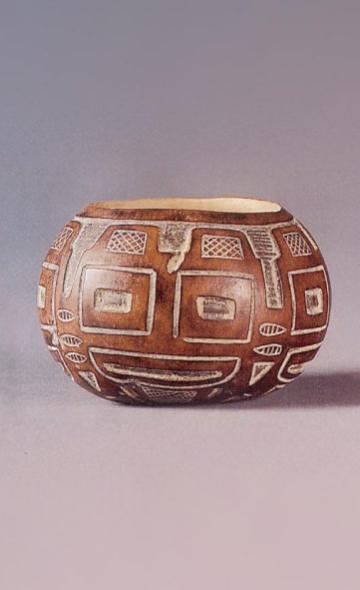

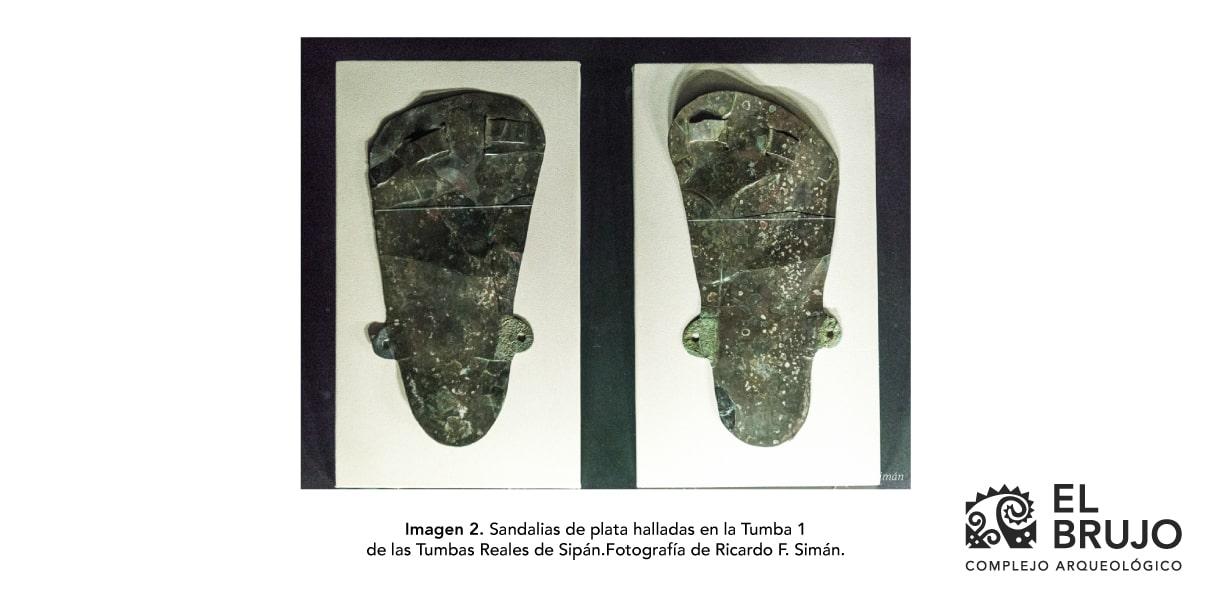

On the north coast, the Mochica (200-800 A.D.) resorted to differentiating in their iconography the lower extremities into sections: knees, calves, feet and shins in scenes of war, rites and sacrifices, suggesting some type of protection (Larco, 1945; Gayoso, 2018). Moreover, from the funerary trousseaus, such as that of the Lord of Sipán in Lambayeque (Alva, 1995), we can affirm the use of footwear in northern Peru.

Walking among the ethnohistorical data

After the conquest, the first chroniclers, Guaman Poma de Ayala, Hernán Cortés, Cieza de León, Bernabé Cobo, and others, described and illustrated in their texts that the people of the New World walked around well dressed and shod (Meseldzic, 1992).

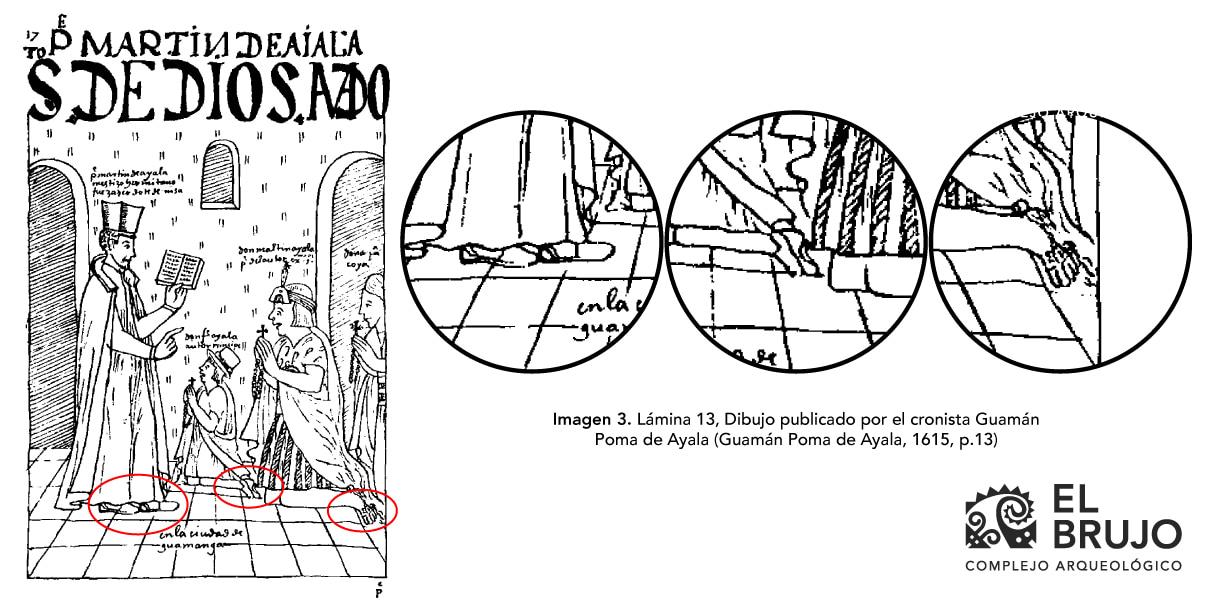

One of the evangelizing scenes that illustrates the diversity of footwear is found in the drawings of the chronicle of Guamán Poma de Ayala (1936 [1615]). Plate 13 depicts a mass in the city of Huamanga conducted by the Father of Martín de Ayala, recognized for wearing a cassock, cape, cap and espadrilles, while his half-brother, Don Felipe, wore European-type shoes. Also, his stepfather, Don Martín de Ayala, wore usutas (shoes), as well as an unku (male’s tunic) (description of the characters from left to right; Gonzáles et al., 2001). This scene demonstrates that footwear is a key element of clothing that provides more information about social distinction in colonial life.

During the colony in Peru, European fashion influenced the manufacture of footwear, evidencing the excellent expertise of the shoemakers. This is how, in the first half of the sixteenth century, artisanal activity was very lucrative due to scarce competition. However, over time, the high demand and incorporation of the indigenous and African population into the trade generated the implementation of the guild system in order to limit the development of local production and restrict raw materials and styles to a social sector in the viceroyalty (Fernández, 2016).

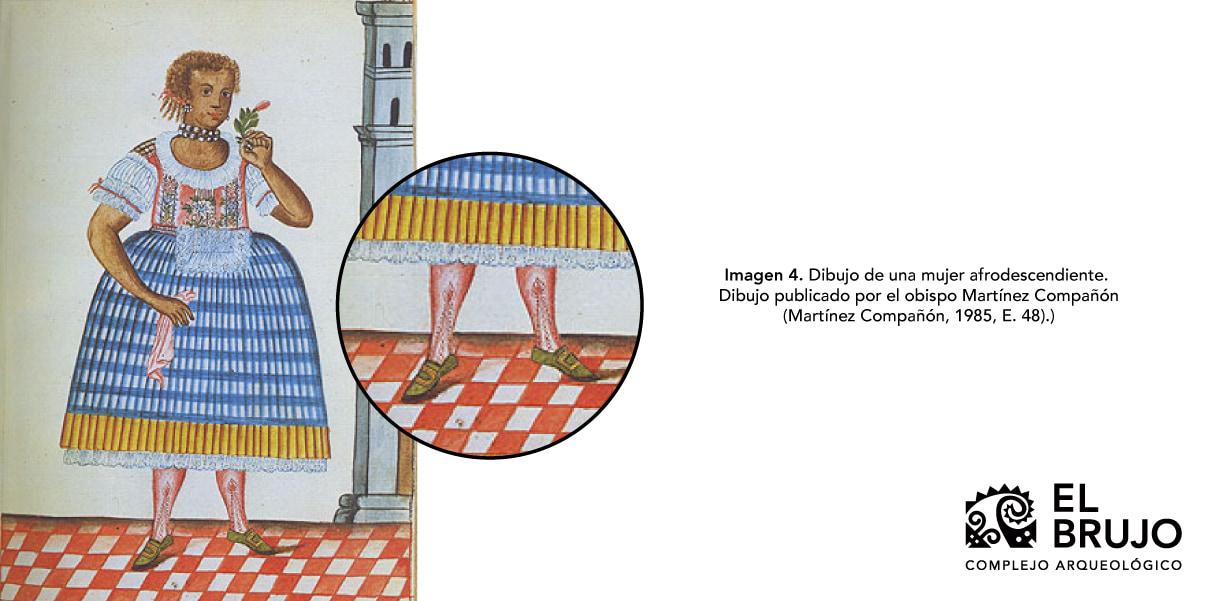

The guild authorities controlled access to the trade, the distribution of raw materials and the guild's own production (ii). In the Truxillo del Perú Codices, illustrated by Bishop Baltasar Jaime Martínez Compañón y Bujanada, pointy shoes with buckles are portrayed as part of the clothing of the epoch (Amat, 2021) during their stay in Peru in the eighteenth century.

Footwear at the El Brujo archaeological complex

The El Brujo's collections feature 35 pieces of footwear that come mainly from colonial contexts. In the collection, we observe the use of two different raw materials for the manufacture of footwear: vegetable fiber and leather, which we will present below.

Piece No. NEBBTX00000-170 is an espadrille (Ruiz, 2014) made of vegetable fiber. The instep, as well as the tie or strap that attaches the shoe to the heel, is made of cotton woven with the technique of interlacing or twisting, while the sole is made of another vegetable fiber (possibly braided cabuya), sewn to give it consistency and shape.

Aside from that, piece No. EBBRA00000-9, is the classic European lace-up, closed-toe or apron-toe shoe, made of goat leather, featuring hand-sowing at the height of the heel to join the pieces with cotton threads. Also, we see linear and circular openings on the instep and tongue to facilitate the perspiration of the foot or to differentiate the design.

Recap

Footwear not only fulfilled a practical function of protecting the foot: it was also a cultural element that reflected the identity, social distinction, skills of the artisan and the social organization for its consumption and production. Moreover, the variability of styles according to the territory and its context was linked to access to raw materials for their manufacture, function and for fashion.

The study of archaeological materials provides valuable sources of information in order to understand, looking at the past, why we dress the way we do at present and what we will wear in the future. Visit the El Brujo archaeological complex and learn more about our collections.

Notes

i. However, we do not disregard the fact that the origin of footwear is ancient.

ii. At the time of the European Middle Ages, the guilds of merchants and artisans were associations of people who exercised the same trade (for example, potters, carpenters, shoemakers, tailors and painters, among others) and enjoyed various privileges, generally granted directly by the king or by the mercantile authorities. During the colonial period in Peru, the guild organization implied the control and oversight by the masters, journeymen and apprentices who worked in the different workshops (Quiroz, 1995).

References

Alva, W. (1995). Royal Tombs of Sipan. University of California Press.

Amat, J. (2021). Footwear technology. The Shoe, a sector with Art and History. Footwear Museum - Ingeniería Amat y Maestre S.L.

Fernández, D. (2016). The interference of the guilds of artisans in the organization of trades in colonial Lima. Social Research, 20(37), pp.233-240.

Gayoso, H. (2018). The clothing of the Moche: an analysis based on the iconography. In S. Uceda, R. Morales and C. Rengifo (Eds.), Research in Huaca de la Luna 2016-2017 (pp. 299-311).

Guaman Poma de Ayala, F. (1936 [1615]). New chronicle and good government, Peruvian illustrated Codex. Paris: Institut d'Ethnologie, Université de Paris.

Gonzáles, C., Rosati, H., & Sánchez, F. (2001). Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala between two worlds. Aisthesis, 34, 206-241.

Larco, R. (1945). The Mochica (Pre-Chimú by Uhle and Early Chimu by Kroeber). American Geographical Society. Buenos Aires.

Ledoux, L., Berillon, G., Fourment, N., Muth, X. y Jaubert, J. (2021) Evidence of the use of soft footwear in the Gravettian cave of Cussac (Dordogne, France). Scientific Reports, 11, 22727. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02127-z

Martínez Compañón, B. J. (1985). Trujillo del Perú: Vol. II (Spanish Agency for International Cooperation).

Meseldzic, Z. (1992). Hides and leathers of pre-Columbian Peru starting eight thousand years ago. Geographical Society of Lima.

Quiroz, F. (1995). Guilds, races and freedom of industry. Colonial Lima. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Ruiz-Barajas, C. (2014). ESPADRILLES: MEMORY OF THE ROADS, FABRIC OF IDENTITIES. Artifices Magazine, 1-13.

Trinkaus, E. (2005). Anatomical evidence for the antiquity of human footwear use. Journal of Archaeological Science, 32(10), 1515–1526. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.04.006

Trinkaus, E., y Shang, H. (2008). Anatomical evidence for the antiquity of human footwear: Tianyuan and Sunghir. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(7), 1928–1933. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.12.002

Volken, M. (2014). Archaeological footwear. Development of shoe patterns and styles from Prehistory till the 1600s. Archetype Publications.

Xesspe, M. (1975). Footwear in ancient Peru. Arqueología PUC: Bulletin of the archaeology weekly, 17, 23-41.

Wilczynski, J., Goslar, T., Wojtal, P., Oliva, M., Göhlich, UB., Antl-Weiser, W., Sída, P., Verpoorte, A., y Lengyel, G. (2020). New Radiocarbon Dates for the Late Gravettian in Eastern Central Europe. Radiocarbon, 62(1), 243–259. doi:10.1017/RDC.2019.111

Researchers , outstanding news