- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The Chicama Valley

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Augusto Bazán Pérez

By Augusto Bazán Pérez

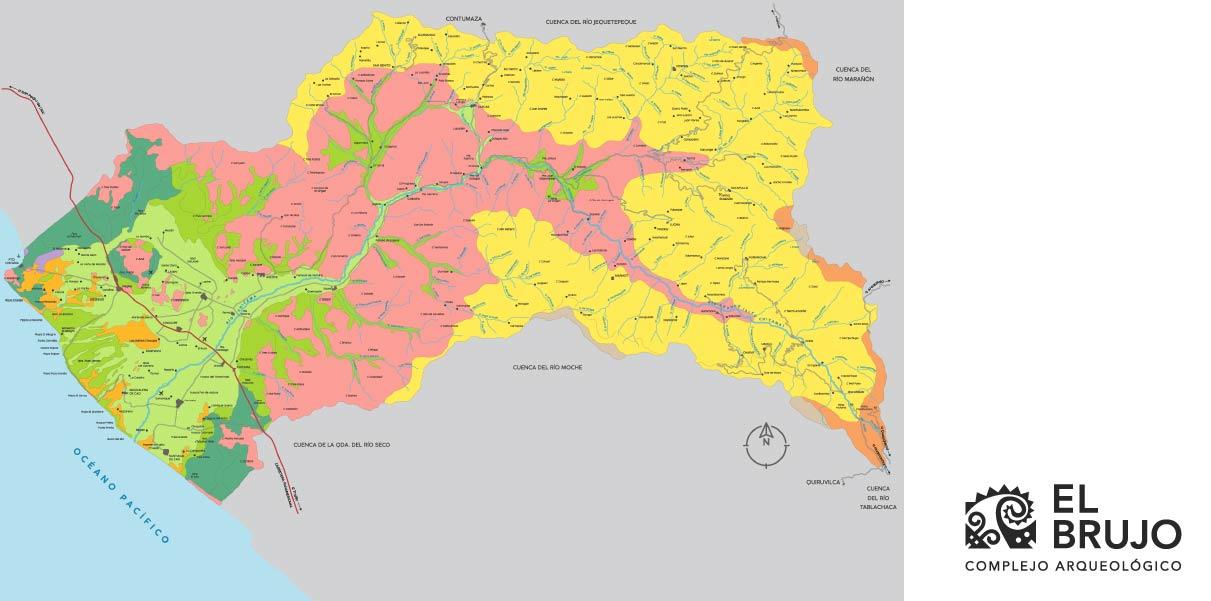

The Chicama Valley is one of the main valleys of the Peruvian coast. It is traditionally associated with the cultivation of sugarcane, the dominant crop in the basin since the end of the 19th century, and its agro-industrial production, whose peak occurred during the period of the large haciendas, such as Casa Grande, Roma, Cartavio, and Chiclín, which disappeared at the end of the 1970s due to the agrarian reforms of General Juan Velazco Alvarado. However, we do not often stop to think about the other most basic aspects of the valley: What is a valley? What is its source? Does it have enough water to irrigate all the agricultural areas it contains? What is its extent? What are its main cities?

What is a valley?

A valley is a depression on the earth’s surface, with an elongate form and inclined toward a lake, the sea, or a closed basin with no exit, in which the water from a river that carries water when it rains (fluvial valley) or from the melting of a glacier (glacial valley) or from a spring tends to flow. Valleys were formed over millions of years due to erosion, among other factors, from the course and force of the rivers’ waters, delineating the “V” shape that they tend to have.

The valleys of the Peruvian coast are always born in the high part of the Andes Mountain Range, and they plow through majestic mountains until arriving at the coastal plains, at the end of which they encounter the sea. Although the depressions and their water are formations defined by nature throughout history, the valleys as we know them are human creations. Around approximately 5,000 BCE, humans learned to produce their own food through agriculture. As population density increased, it was necessary to extend the fields that were cultivated to feed more people. This expansion of the agricultural frontier is connected to the idea of taking the water from the rivers to spaces that were progressively farther away, toward the margins of the valleys, and thus sustaining larger populations.

The valleys are conceived, then, as a cultural formation, where the actions of nature (earth and water) and the actions of humans (irrigation, agriculture, cities, and others) are combined. As is evident, the expansion of the agricultural frontier is easier in flat areas, in other words, in the highland plains or on the “coast”, stealing space from the deserts and the arid plains. It is because of this that the valleys tend to be more commonly identified through their lower segments, close to the sea, where they also tend to have important cities.

What is the source of the Chicama River?

The Chicama River’s source is at the mines of Callacuán, at 4,100 meters above sea level, in the highlands of Quiruvilca, in the district of Santiago de Chuco; it is worth noting that its source is close to that of the Moche River, which gives life to the valley of the same name, neighboring the Chicama Valley to the South. Its course is similar to a large inverted “U” and is very long; it flows for approximately 150 kilometers before reaching the Pacific Ocean. As with all rivers, it is fed by various rivers of a smaller scale, which at the same time flow down through minor valleys or gullies. Its principal tributaries are, from the right-hand shore to the East, Chuquillanqui and San Felipe (which drain into it near the towns of Chuquillanqui and Molino) – from which the name of the Chicama was adopted from in the old Hacienda Tambo – Ochape, and Cascas (near the town of Cascas), and Santanero (also known as San Benito, which drains into it near Jaguay). On the left-hand side, the Quirripano River drains into it at Pampa de Jaguay.

The valley begins to broaden around the location of Sausal, where the mountains start to disappear and the river reaches the coastal plains, achieving its maximum width in the highland plains, where the towns of Ascope, Chocope, Paiján, and Cartavio are found.

It is important to note that all the valleys are traditionally divided into three segments, with the lower valley being associated with the coastal plains and the majority of the available agricultural lands. This segment tends to be hot and arid due to the lack of rain, but is linked to other economies such as fishing due to its proximity to the sea. The middle valley, associated with the foothills of the Andes Mountains, or the transition between the coast and the highlands, is hot and sheltered, thanks to being bordered by the mountains of the lower sections of the range. The upper valley is in the Andes mountains, the highlands of the country which are rainy during the summer, incessantly sunny during the day and with very low temperatures at night.

Does it have enough water to irrigate all the agricultural areas it contains?

The Chicama River has a torrential cycle, but it is not constant. In other words, 70% of its flow appears during the summer, between the months of January and April, when it rains in the highlands. The constant expansion of the agricultural frontier, which has not ceased in hundreds of years, means that water use by the populations of the valley is in deficit; more water is needed than the Chicama provides. For this reason, large irrigation projects are needed such as Chavimochic, which irrigates lands associated with the Chicama, Moche, Viru, and Caho Valleys with water from the mighty Santa River, in the region of Ancash; also, it is necessary to technify irrigation in the lower valley, where the monoculture of sugar cane is a large problem for hydraulic conditions, along with the indiscriminate presence of wells that suck water from the subsoil, also called the water table, constantly weakening it.

What is its extent?

The Chicama Valley covers a total of 76,963 hectares, of which 57,343 are apt for agricultural use under irrigation. It is important to note that the agricultural potential of the middle and upper valleys is limited, due to the presence of steeply inclined mountains and the fact that, although the lower valley presents better conditions, there is a large coastal fringe on the northern side of the river, between its mouth and the current Chicama Port, that presents serious problems of salinity in soils, which become unsuitable for agricultural use. Currently, this zone is mostly used for ranches.

What are its main cities?

Usquil and Quiruvilca are located in the upper Chicama, highly associated with the mining activity located at the head of the basin, which is risky for the hydraulic sustainability of the valley. In the middle valley there are Cascas, a town that is well-known for its winegrowing industry, and Sausal. In the lower valley, on the coast, where it is the widest, there are cities associated with the industrial production of sugar cane and its derivatives: Casa Grande, Paiján, Cartavio and Ascope. (ONERN 1973)

Researchers , outstanding news