- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The lunar animal: a northern tradition

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Carlos Fuentes Romero

By Carlos Fuentes Romero

“[…] while modern man, despite considering himself as the result of the course of universal History, does not feel obliged to know it in its entirety, the man of archaic societies is not only obliged to recall the mythical history of his tribe, but periodically updates a large part of it "

Mircea Eliade, Myth and Reality (1992)

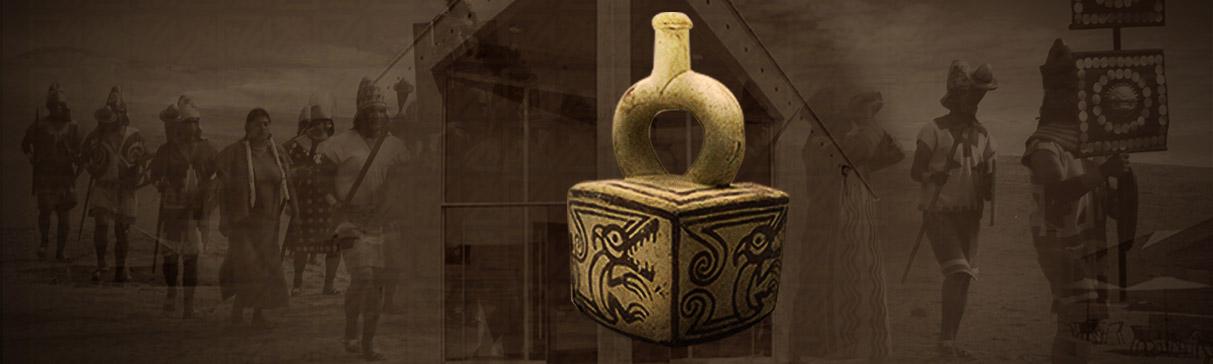

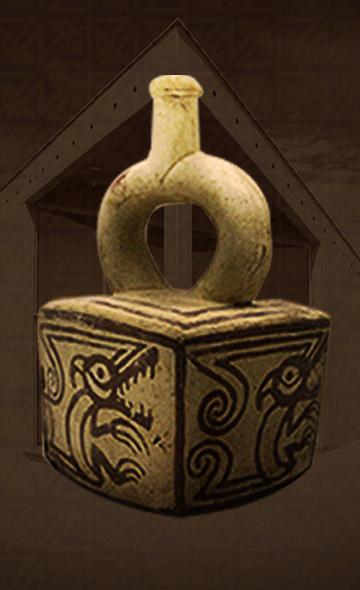

The wide variety of images captured by the Moche on different objects (ceramics, lithics, metals, textiles, etc.) represent one of the most common and well-known evidences of the history of ancient Peru. The El Brujo Archaeological Complex (CAEB), has a vast quantity of Moche ceramics in which not only can one observe the high artistic quality that fills and satisfies our needs for aesthetic contemplation, but is also an important material evidence for understanding a little more the conception of one’s world.

The so-called "lunar animal" is one more example of the Moche mythological and social complexity. Aside from having been profusely represented in the CAEB, its concept was used and expressed throughout the entire Peruvian north coast during various periods of pre-colonial history, with particular emphasis during the Early Intermediate (200 - 800 AD approx.). In this article, we present some ideas that will allow us to learn a little more about this mythical being in the history of ancient Peru.

Iconography: the expression of images

Images are a valuable source of information. As archaeologists, interpretive work –the core part of the profession– requires much patience and creativity, all the more so when dealing with remote scenarios or epochs, where the lack of a written and formal language does not allow us to see a complete panorama of life in the past, leaving to (well supported) interpretive imagination the understanding of the past.

It is evident that the work goes beyond (simply) observing and concluding. In order to understand these images, it is necessary to distance ourselves from naive interpretation, that is, that which is based on our categories. In that sense, it is better to assume that they were made in a general context thought of and imagined by their producers. The task here is to reconstruct the context in order to rescue the meaning of the images (Golte, 2015).

What is the lunar animal?

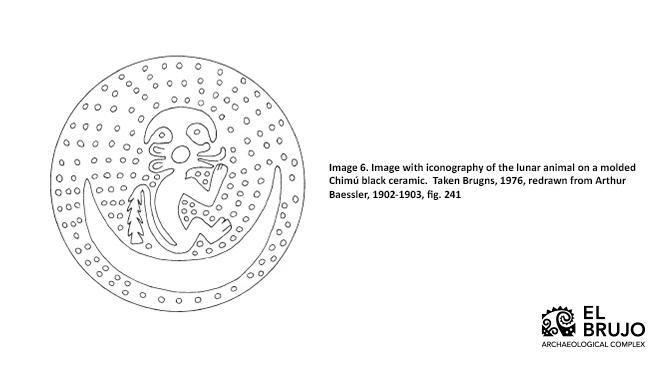

The name "lunar animal" was given in 1950 by Gerdt Kutscher (Mackey & Vogel, 2003). This notwithstanding, over the years, various researchers have called it in different ways, depending on the interpretation given by each one: crested animal, animal on the moon, quadruped in the shape of a crested dragon, crested feline, lunar monster, lunar devourer, and even "griffin", etc. (Bruhns 1976, Benson 1985, Gutiérrez, 2002). It is evident that a consensus does not exist yet.

How is the lunar animal represented? Mackey & Vogel (2003) present us with a series of characteristics that would allow us to identify this mythical being:

1. Four legs

2. Long protrusions that extend from its head and tail

3. A square muzzle

4. Clear and visible teeth

5. An arched and sinuous body

6. Long claws

7. A variety of ornamentations such as a serrated top of the back and tail

These characteristics are basic, although not excluding; there are other less common features in the different representations of the animal.

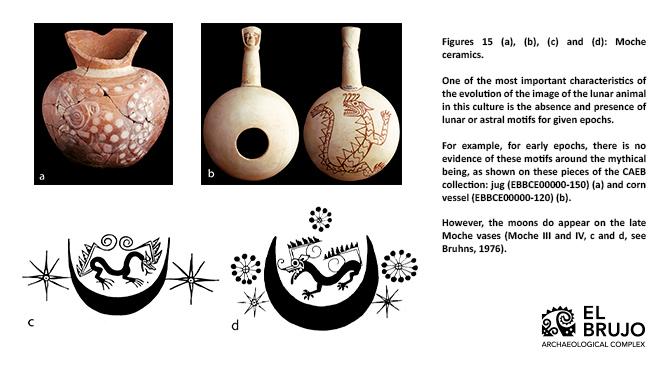

Now that we know its main characteristics, it is worth asking ourselves: what animal does it represent? For Mackey and Vogel (2003), the animal in question is the wildcat (Oncifelis colocolo); following the same line of felines, Tello identified the animal as a jaguar (Tello, 1923, cited by Bruhns, 1976). Narváez (2014). However, he identifies the lunar animal as a Peruvian hairless dog, based on iconography and ethnographic records. Furthermore, Ugalde (2006) proposes that the animal is actually a possum and that it would have a northern origin (Ecuador-Colombia). Finally, for Hocquenghem (1987), there is an association of this animal with the “deer-snake-jaguar” according to its composite structure, or, outright, a being created with different parts of other animals (Menzel, 1977, cited by Mackey & Vogel , 2003). And why lunar? Well, due to the presence of this star associated with the images of this mythical being in Moche ceramics, as of the the Moche III and Moche IV style phases (Bruhns 1976).

The Lunar Animal in Space and Time

The representation of the Lunar Animal is a tradition that lasted a long time in a very extensive territory. Contrary to popular belief, not only the Moche represented it, but also other social groups in other spaces and times. The Tumaco-Tolita, Recuay and Chimú cultures depicted this mysterious personage in their art and beliefs.

• Tumaco-Tolita culture (Colombian south coast and Ecuadorian north coast, 350 BC - 350 AD approx.)

The name of this culture responds to two pre-Hispanic centers of high cultural influence along the Pacific coast of northern South America and is temporarily located in the Regional Development period (Patiño, 2003; Ugalde, 2006).

According to Maria Fernanda Ugalde (2006), the fabulous animal represented has been, probably, inspired by a possum. Although there are previous studies that affirmed the association of this animal with the Recuay iconography, it was not linked with the Tumaco-Tolita (See Gutiérrez, 2002).

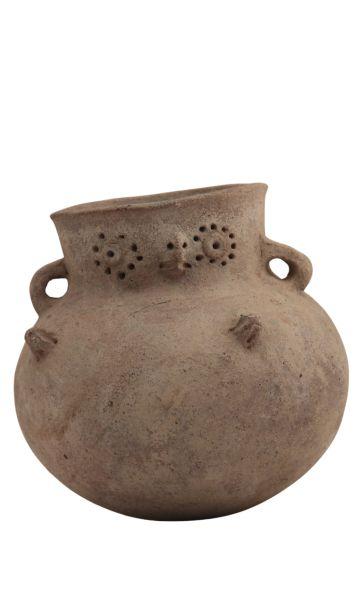

• Recuay (north-central Peruvian highlands, 1 – 800 AD approx.)

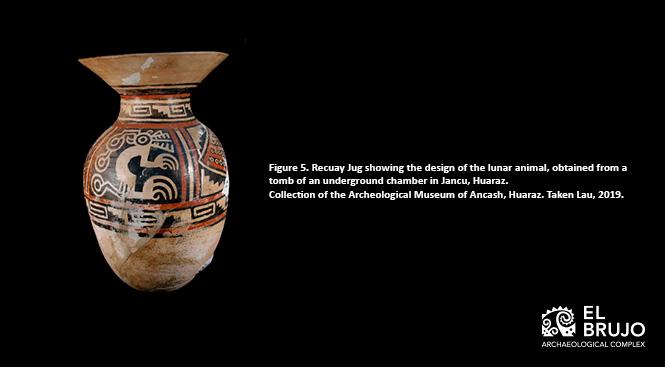

The Recuay society is the one that has depicted the lunar animal the most, after the Moche –in the Central Andes. The so-called “Recuay tradition” developed temporarily in the period known as Early Intermediate (Lau, 2002).

The most striking feature of the appearance and recurrence of the lunar animal in Recuay iconography is the absence of the moon as a symbol associated with the animal. The lunar or crawling animal is represented as a central motif in Recuay funerary ceramics (Lau, 2002) and although it is believed that it has only been depicted in ceramics (See Ugalde, 2006), it is also evidenced in sculptures and textiles (Lau, 2002).

• Chimú (Peruvian north coast, 1000 – 1460 AD approx.)

Placed within the so-called Late Intermediate period, the Chimú took up the symbolic tradition of the lunar animal after the collapse of the Moche in the Moche, Chicama and Virú valleys (Castillo, 2018). This people made relevant iconographic changes compared to their predecessors, as a more anthropomorphized figure of this mythical being (Mackey & Vogel, 2003).

Other of the most important variations we can observe are in the head, a more pointed snout and the presence of the growing headdress of a Chimú deity instead of the crest that it used to have; and the tail, with segmented designs (Mackey & Vogel, 2003).

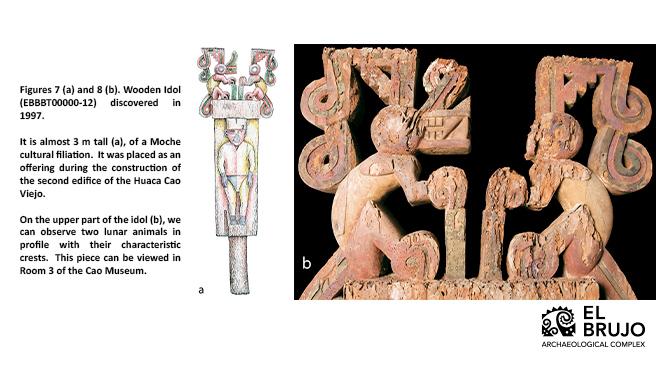

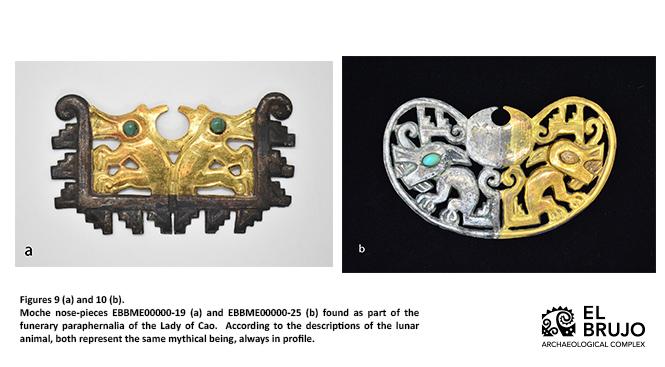

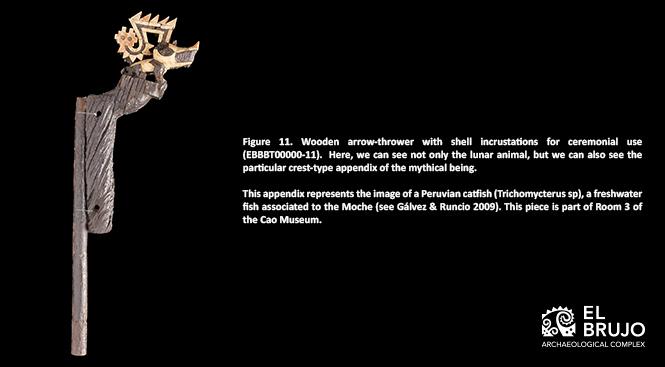

The lunar animal at the El Brujo Archaeological Complex (CAEB)

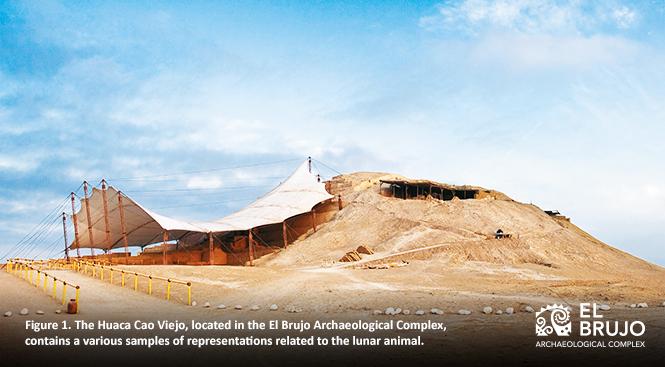

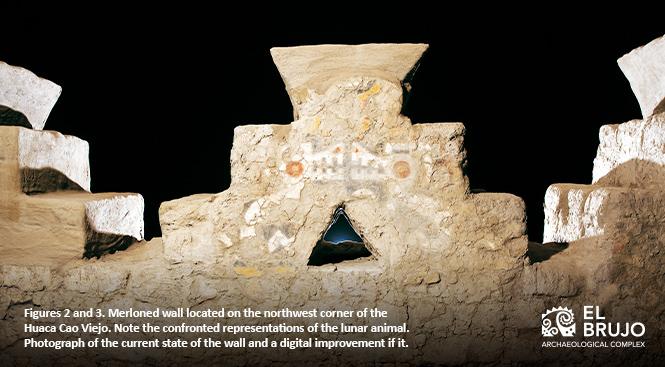

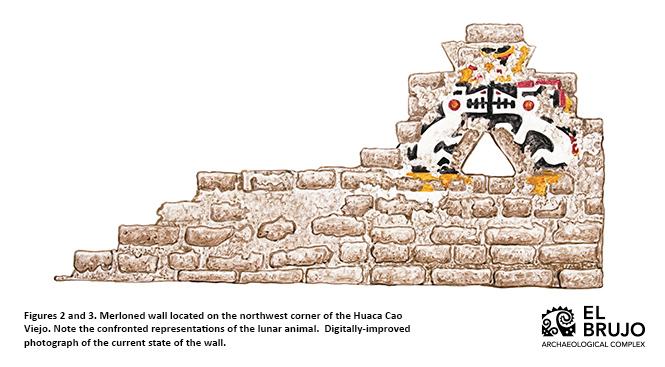

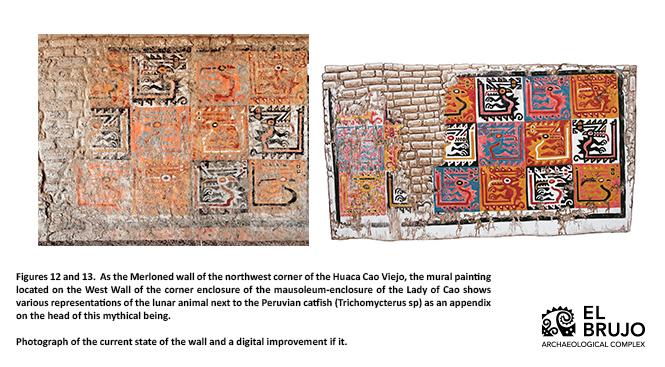

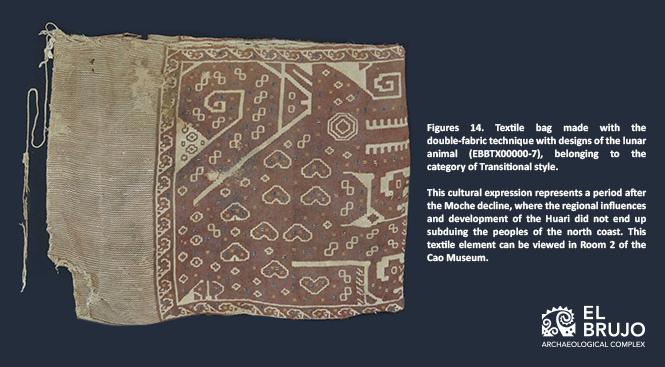

What do you think of the trip so far? Interesting, isn’t it? Now let's take a look at the main course in this journey: the Moche and Transitional archaeological remains, where we can see the representations of the lunar animal found in the El Brujo Archaeological Complex. The physical medium on which they were depicted ranges from the classic ceramic pieces to part of the architecture of the Huaca Cao Viejo.

Conclusions

At the end of this tour, it is worth asking ourselves: is the lunar animal a natural specimen taken as a model by the ancient inhabitants of the Central Andes? Or was it, rather, a mythical being in the whole sense of the word; that is to say, one more creation of the human imagination based on various animals that inspired it? A valid question, but one with no clear answer for the moment. The lack of studies –and the absence of zoological material evidence that meets all the aforementioned characteristics– is the main barrier to overcome in order to understand this personage. Even more so when the records –according to some researchers– indicate the existence of representations of lunar animals not only in the aforementioned cultures, but also in the Vicús and Gallinazo cultures, and even part of the colonial era (Mackey & Vogel, 2003).

Knowing, but also understanding the complex situation of the ancestors is a basic task in order to understand the world of today. Just as today's societies recall their past loved ones, yesterday's societies recalled mythical events lest they be forgotten, in that form of transgression of their divine nature, of their origin as such (Eliade, 1981). This updating of myths is essential to understand the mechanism of continuity of religious beliefs and experiences in societies. The lunar animal is the clearest example of this: its persistence in different cultural developments demonstrates a tradition based on the belief in certain elements considered sacred to them.

The CAEB, through its archaeological collections, holds within its facilities various mysteries that still remain to be solved. Questions that with the right dose of curiosity and convincing information can lead to clarifying answers.

References

Benson, E. (1985). The Moche Moon. Recent Studies in Andean Prehistory and Protohistory: Papers from the Second Annual Northeast Conference on Andean Archeology and Ethnohistory, 121-136.

Bruhns, K. (1976). The moon animal in the northern Peruvian art and culture. Ñawpa Pacha, 14, 21-39.

Castillo, F. (2018). Typology and serialization of ceramics from the Chimú cemetery of Huaca de la Luna, Peru. Bulletin of the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art, 23 (2), 27-58.

Eliade, M. (1981). The sacred and the profane. Editorial Guadarrama.

Eliade, M. (1992). Myth and reality. Editorial Labor.

Gálvez, C. & Runcio, M. (2009). The Life (Trichomycterus sp.) And its importance in Mochica iconography. Archaeobios Journal, 3, 55-87.

Golte, J. (2015). Moche, cosmology and society. An iconographic interpretation. Editorial Fund, Institute of Peruvian Studies.

Gutiérrez, A. (2002). Gods, symbols and food in the Andes. Man-fauna interrelation in pre-Hispanic Ecuador. Editorial Abya-Yala.

Hocquenghem, A. (1989). Mochica iconography. Editorial Fund, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Lau, G. (2002). The Recuay Culture of Peru's North-Central Highlands: A Reappraisal of Chronology and Its Implications. Journal of Field Archeology, 29, 177-202.

Lau, G. (2019). The Recuay culture: a short essay. Pre-Hispanic Peru: a status on the matter, 208-233.

Mackey, C. & Vogel, M. (2003). The Moon over the Andes: A Review of the Lunar Animal. Moche: Towards the end of the millennium. Proceedings of the second colloquium on Moche culture, 1, 325-342.

Narváez, A. (2014). Gods of Lambayeque. Introduction to the Study of the Late Mythology of the North Coast of Peru. Ministry of Culture of Peru – Naylamp Lambayeque Special Project.

Patiño, D. (2003). Pre-Hispanic Tumaco. Settlement, subsistence and exchange on the Pacific coast of Colombia. Editorial University of Cauca.

Ugalde, M. (2006). Dissemination in the period of Regional Development: some aspects of the Tumaco-Tolita iconography. Bulletin of the French Institute of Andean Studies, 35 (3), 397-407

Researchers , outstanding news