- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- How are the cultures in ancient Peru recognized? Estimation of social groups, territory, and time in archaeology

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

Magdalena de Cao to Once Again Host an International Mural Art Gathering ...

Explore El Brujo Through Virtual Tours: Culture and History at a Click ...

To receive new news.

By: Augusto Bazán Pérez

By Augusto Bazán Pérez

Wiese Foundation | El Brujo Archaeological Complex

Director of Investigation

What do we call “cultures” in ancient Peru?

Traditionally, the term culture refers to a social group that shared the same beliefs, belonged to the same economy, spoke the same language, and lived within a same sociopolitical system. Basically, a people that shared the same identity. This static vision of a society is constantly under debate, since “culture” is a word that has too many meanings, making it difficult to use. Currently, other terms are preferred when referring to the ancient peoples studied by archaeology (societies, social groups, sociopolitical formations, etc.), considering that the old concept of culture is very monotonous and tends toward nationalistic ideals which are out of date in the social sciences. It is understood that within social formations there is much space for diversity and dissent, without losing those cultural characteristics that are held in common, which identify them in a particular way, and which are noted in their material culture: in the form and style of their ceramics, in how they built their temples and houses, in the way in which they buried their dead, in their social structures and levels of inequality, in their diet and quality of life, etc.

How are they identified?

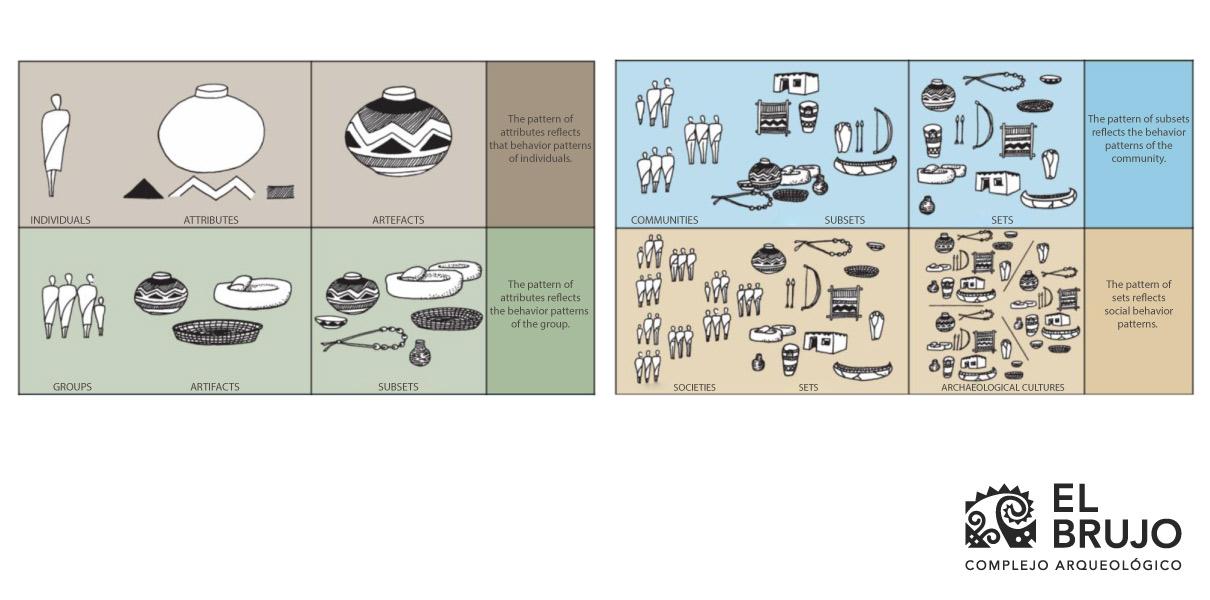

Precisely through their material culture, or those things or objects that they produced and which endured until our time. Archaeologists recover material culture, in general, through archaeological excavations, and they classify the evidence according to different criteria. The general idea is that characteristics in common define a same social group. This similarity is guided predominantly by style, understood as a particular way of making and decorating an object under social guidelines. Style is embodied in diverse material media. When we refer to a same style of ceramics, architecture, or figurative or iconographic art, we are talking about a set of knowledge, beliefs, and techniques shared by a same society. For example, the Lambayeque Culture is defined specifically by a type of ceramics and architecture. Lambayeque ceramics have various attributes of style and form (its typical form is Huaco Rey), and they are found associated with certain spaces, e.g., temples or ceremonial centers, with very distinctive features (pyramids with smooth and inclined sides, with the presence of ramps and made with planoconvex adobes without molding). Figure 1. Terms used in archaeological classification that led to the identification of cultures and societies, from the basic individual attributes (form, decoration) of a vessel to the complete archaeological culture. Taken from (Deetz 1967:107; Renfrew and Bahn 2012:118).

Figure 1. Terms used in archaeological classification that led to the identification of cultures and societies, from the basic individual attributes (form, decoration) of a vessel to the complete archaeological culture. Taken from (Deetz 1967:107; Renfrew and Bahn 2012:118).

How do we determine where they developed?

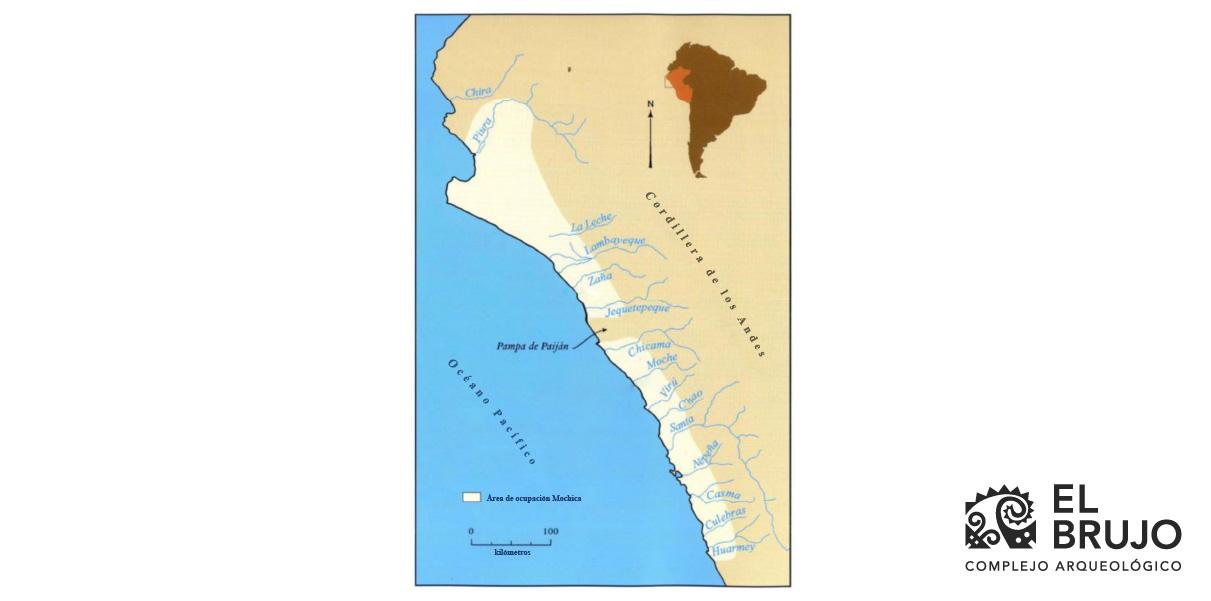

The presence of the same materials previously indicated, in certain geographic spaces, gives an idea of the territorial extent of a certain social formation, and/or its areas of influence. For example, Moche ceramics, as well as its characteristic monumental architecture, do not exist to the North of the Piura Valley or to the South of the Huarmey Valley. Furthermore, they do not exist in the high valleys of the basins that descend toward the ocean; in other words, they never dominated the highlands. Where this characteristic material culture is not frequent but rather coexists with other types of expressions, these can be interpreted as peripheral areas or ones of tenuous influence rather than direct control.

Figure 2. Extent of the Moche Culture. Material culture with Moche characteristics (ceramics, architecture, burials, works of metallurgy, etc.), as a set, are not found to the North of the Piura Valley or to the South of the Huarmey Valley. They are also not found in the highlands of the Andes beyond the middle parts of the northern valleys that descend to the Pacific Ocean. Taken from (Donnan and McClelland 1999:12).

How do we determine when they lived?

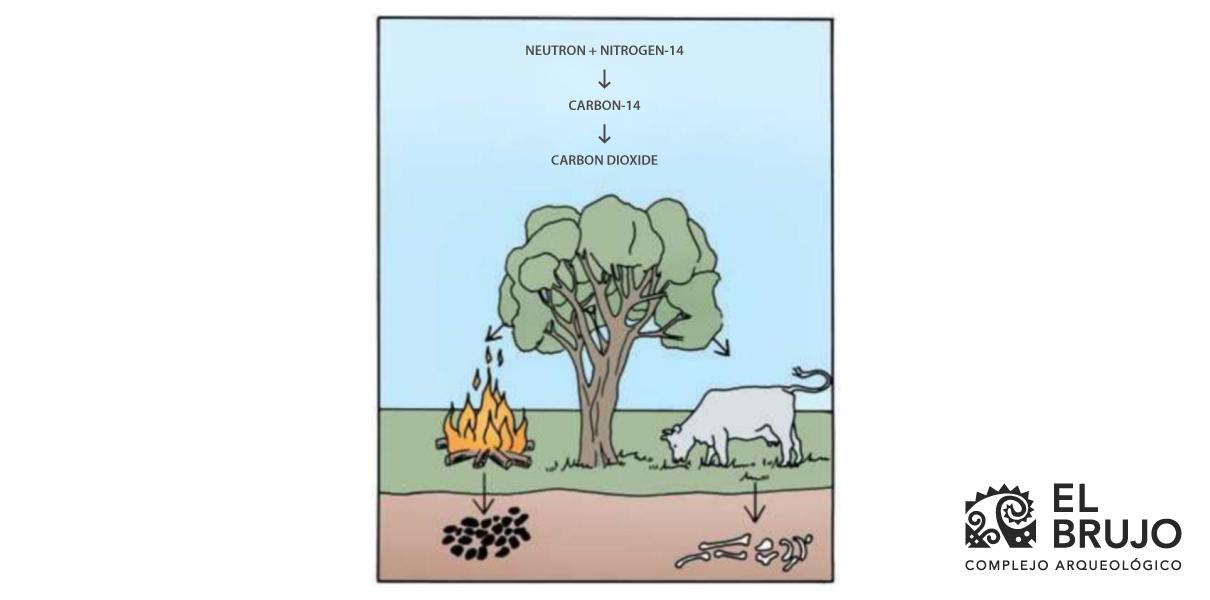

Cultures, just like living beings, complete the same life cycle, in general terms: they are born, they reproduce, and they die. The collapse or disappearance of a society, however, just like the death of a living being, is not definitive, but rather leaves a legacy. Organizations change, but people persist and preserve traces of their predecessors: technology, knowledge, certain institutions, and beliefs that can survive even into the present. And the “end” of a culture is, without a doubt, the start or the formation of another. To know when the birth and fall of a social formation happened, archaeology preferentially uses Carbon-14 dating. This physiochemical technique determines the time passed between the death of an organic organism and the year 1950 (the present, or the date of the invention of the technique). Through cultural stratigraphy, the principle that allows for the determination that a cultural expression precedes another through superposition, the oldest expression of a culture is determined, immediately after a previous culture, and its latest expression is determined, before the appearance of a distinct posterior cultural expression. If samples from both parameters are dated, we can understand the duration of the social phenomenon that we are analyzing. For example, in the Chicama Valley, the earliest Moche evidence corresponds to 2000 BCE, while the latest corresponds to 700 CE, approximately. It is important to point out that the temporal ranges are not the same in all the valleys, so research must be rigorous and constant to obtain more samples and, in this way, refine the chronologies, or the duration and temporality of the social phenomena studied in pre-Hispanic history.

Figure 3. Radiocarbon, or Carbon-14 is produced in the atmosphere and absorbed by plants through carbon dioxide, and by animals through the consumption of plants or other animals (Renfrew and Bahn 2012:137). The consumption of Carbon-14 stops when the animal or plant dies. The quantity of C-14 in a dead organic material determines the amount of time that has passed between its death and the present.

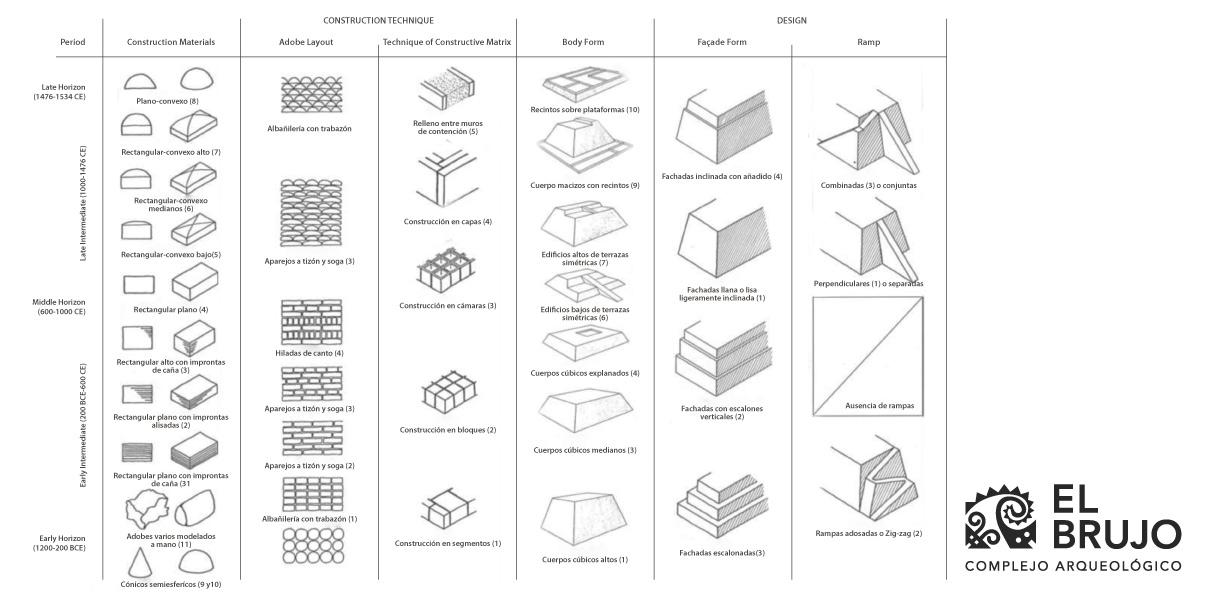

Figure 4. An example of the changes detected in the constructive elements and monumental architecture of the North Coast, created by Marcus Reindel in early 1990. Over a range of almost 3,000 years, it identifies the changes that occurred in the shapes of adobes, the way in which these were place in constructions, the type of public architecture built and its facades, as well as the changes or diverse types of ramps used to access the monuments. (Reindel 1993:368).

Epilogue

The identification of cultures that did not have writing, as well as their study from different points of view (chronology, diet, sociopolitical systems, religion, funerary patterns, et.) is the object of study of archaeology. This summary outlines the basic aspects of the study of a pre-Hispanic society. It is important to understand, however, that the sample that archaeologists analyze is getting progressively smaller. The proof or evidence of ancient occupations is constantly decreasing due to time, looting, the systematic destruction of archaeological sites that fall victim to uncontrolled urban growth, and the lack of regulation of the advance of public and private projects, among other factors. Therefore, the recording of these cultures must be exhaustive, and must promote studies that allow for the recovery of more data, thus allowing us to better understand the societies that came before us and from which we came.

Researchers , outstanding news