- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Chronology: The Lambayeque Period (900-1350 CE)

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Rubén Buitron Picharde

By Rubén Buitron Picharde

The Wiese Foundation | El Brujo Archaeological Complex

As is known, well before the existence of the Inca, in the different corners of the Andean territory, multiple cultures flourished and distinguished themselves by their levels of organization, complexity, and economic activity.

A clear example of this was the Lambayeque culture, a society that developed on the Peruvian North Coast between 900 and 1350 CE. Their most well-known economic activities were metalwork, stonework, ceramics, and intensively irrigated agriculture; however, they are principally known for their ceremonial knife: the Tumi (figure 2).

Figure 1. Ceremonial “Tumi” knife. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Currently, there is a debate among researchers as to the terminology used to refer to this culture. On one side, the term “Lambayeque” is used, supported by Rafael Larco (1948), and on the other side, the term “Sicán” is supported by Izumi Shimada (Shimada 1995, 2014), with the former being most widely used.

It is important to note that this discrepancy is not only terminological, but also involves foundational and chronological aspects and depends greatly on the areas where the studies are carried out (center vs. periphery).

For practical purposes, we will use the term “Lambayeque” to refer to the set of cultural expressions that began during the Intermediate Period (800-900 CE) (Rucabado & Castillo 2003) and lasted until the expansion of the Chimú Empire in the northern valleys, around 1375 CE.

The Lambayeque culture developed largely on the North Coast, from Alto Piura to the Chicama Valley in La Libertad. However, its political and economic nucleus was in the La Leche and Lambayeque Valleys, specifically in what is currently known as the Sicán Archaeological Complex in the Pómac Forest (middle La Leche River valley), Túcume (lower La Leche River valley), and the Chotuna-Chornancap Archaeological Complex (9 km from the city of Chiclayo).

These are large complexes with more than 30 monumental buildings, constructed primarily of adobes. Other Lambayeque complexes, outside of the nucleus of influence, include Úcupe (lower valley of the Zaña River), Pacatnamú (lower valley of the Jequetepeque River), and the Rosario Group (lower valley of the Chicama River) (Figure 2).

In all these valleys, there are still a significant number of sites from the Lambayeque Period, but they have been severely affected by agriculture and urban growth, reduced to their minimum expression.

1.jpg)

Figure 2. Aerial photo of the Rosario Group. Source: Kosok 1965: 109.

These settlements were not necessarily all contemporaneous, based on the presence of cultural styles and radiocarbon dates. Izumi Shimada (1995) identified three well-defined phases.

- Early Sicán (800-900 CE): This phase saw the decline of the old Moche order and the confluence of various cultural styles, principally Huari. It was a time of great interaction where there was not yet evidence of a single hegemonic style.

There was the appearance of a type of globular bottle with a face with birdlike features including elongated or winged eyes. According to Shimada, this bottle was the direct antecedent of the celebrated “Huaco Rey”, which would become the most-consumed artifact of the Lambayeque elite later on.

A large part of the evidence for this phase comes from cemeteries (Franco et al. 2007; Prieto 2014). There are scant buildings to be able to infer an architectural pattern. One of the few architectural pieces of evidence clearly linked to this phase are the buildings adjacent to the Intermediate Cemetery at San José de Moro (Prieto 2014).

- The Middle Sicán (900-1100 CE): There is evidence of a notable economic and cultural development with the site of Sicán as its principal center. There is evidence of high levels of specialization in production activities stemming from agriculture and the construction of extensive irrigation canals.

According to Wester (2018), the Lambeyeque implemented a series of irrigation projects on an intervalley level, such as the Taymmi, Inalche, Cucureque, and other canals. In the case of the Chicama Valley, the great Ascope Canal System (Figure 3) stands out, which irrigated the Mocán plains.

2.jpg)

Figure 3. View of a segment of the Ascope Canal System. Photo: Rubén Buitron.

The expansion of large-scale agriculture allowed for the development of other economic activities such as mining, metalwork, textiles, monumental architecture, and long-distance trade. In metallurgy, large foundries where arsenic-copper was produced have been identified in places such as Sicán.

This great advance created a more ductile and resistant metal during the metallurgical process. The possession of these types of artifacts became synonymous with prestige, as is demonstrated by the tombs of the elite at Huaca Loro, which contained abundant lance points, created with metallic alloys, that weighed between 250 and 500 kg in total (Bezur 2014).

The buildings of this time shared some architectural components. The main building was composed of a truncated pyramid, made through the superposition of a series of platforms. On its top, beautifully decorated rooms with representations of the current deities were built.

To access this pyramid, there was a large ramp, which in general was straight, though there are some cases of zigzag ones, as is the case at Huaca Loro (Shimada 1995). These architectural components tended to neighbor a grand, rectangular walled plaza. However, the greatest indicator at the level of construction is the use of plano-convex and convex adobes, used both in the political centers and their peripheral settlements (Figure 4).

1.jpg)

Figure 4. Seriation of adobes at Batán Grande (Shimada 1995) and in the Chicama Valley (Gálvez and Castañeda 2014).

To achieve levels of cohesion and centralization in production, an ideological consensus was established that allowed for the strengthening of the elite. One of these conventions was the foundational discourse linked to the being represented in the “Huaco Rey” (Figure 5).

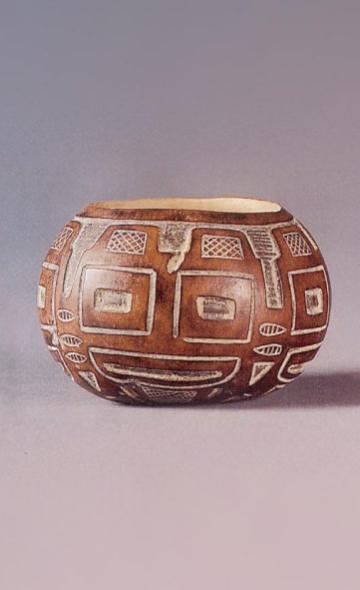

This is a black ceramic bottle (produced in a reduction oven) with a globular body and a stirrup or bridge handle, with the representation of a mythic character with “winged” eyes, generally flanked by swimming or flying people.

.jpg)

Figure 5. Huaco Rey recovered from Burial 23-1992 from the Lambayeque cemetery at Huaca Cao Viejo.

The development of a solid productive base, the establishment of infrastructure for the administration of resources, and the constitution of a shared system of beliefs promoted the development of a classist society. This is evidenced in the fastuous tombs discovered at Huaca Loro (Figure 6).

1.jpg)

Figure 6. Elite burial at Huaca Loro in the monumental archaeological zone of Batán Grande. Source: Shimada 1995: 55.

However, around 1100 CE, several social changes took place in the political capital that interrupted the chain of production for prestige goods, which in addition to the effects of a mega El Niño led to the collapse of the elite at Batán Grande (Shimada 2014).

- Late Sicán (1100-1375 CE): After the abandonment of various of the main buildings at Sicán, the elite was reconstituted in two large settlements, at the Túcume and Chotuna-Chornancap archaeological complexes. This new composition brought with it a severe weakening of the classic Sicán deity, and abstract and geometric designs were preferred.

In spite of this, there is evidence of a reestablishment of the productive activities to provide the elite with prestige goods again. This is evident in the luxurious tomb of a female individual at Chornancap (Wester 2018).

The Lambayeque presence was not limited to the northern valleys, but rather reached the southern zones such as Pachacamac (Segura and Shimada 2014). Meanwhile, in the North, there is evidence at Alto Piura, though the presence of exotic goods (Spondylus princeps and Conus fergusoni) recorded from the tombs leads us to believe that they extended to the north of the equator. It is probable that the dominion of this long-distance trade network prompted its conquest by the Chimú Empire around 1375 CE.

The Lambayeque at El Brujo

As indicated above, the Lambayeque occupation had its southern limit in the Chicama Valley. After the abandonment of the Moche settlements at El Brujo, there was a reconfiguration of power in the valley and the construction of new buildings with their own characteristics.

One of the most notable post-Moche centers was the Rosario Group, a complex that includes the El Salitral, Ongollape, La Leche, and Rosario Huacas. Although they have not been systematically excavated to date, the primary use of plano-convex adobes and ceramic fragments found on the surface suggest that this complex corresponds to the Lambayeque Period (Gálvez and Castañeda 2014).

Among the other monumental sites are the Tres Huaca Complex, Huaca Cucurripe, Mocollope, Licapa, Huaca Colorada, and the La Laguna Complex. The Ascope Canal System also stands out, which according to radiocarbon dates (Huckleberry et al. 2018) was built during this time.

This represents a large-scale project that had the objective of irrigating extensive plains to the northeast of the valley. On an architectural level, the majority of buildings correspond to stepped pyramids with access ramps; some of these, such as Huaca Colorada, are located adjacent to a large, rectangular, walled plaza, but were bordered by the monoculture of sugar cane that dominated the valley.

But, as we have noted, the majority of these sites have not been excavated; this is the reason that the clearest evidence for the Lambayeque Period is found at the cemetery that covered the northern face of Huaca Cao Viejo at the CAEB.

This cemetery consisted of around 500 burials (Mujica 2007). The great majority of the burials were individuals, with a few exceptions. In its interior, the majority of the individuals were found flexed and wrapped using standardized techniques that sought to give human attributes to the mummy bundle (Figure 7).

The objects that accompanied the mummy bundle were gourd containers, camelid heads and feet, plates of the coastal Cajamarca style, small pots with stamped decoration, and the celebrated Huaco Rey.

Figure 7. Typical components of a Lambayeque burial from Huaca Cao Viejo.

As we have seen, the Lambayeque culture represents a time of reorganization of the northern societies after the Moche. They managed to establish their own cultural identity that allowed for the development of some productive activities at scales never before seen.

While they are known for their beautiful works of metallurgy, it is important to also recognize their hydraulic advances, intensive agriculture, and measured management of the environment, knowledge which is very useful in our times (Goldstein 2014).

Bibliography

Bezur, A. (2014). La tecnología y organización de la producción de aleación de cobre de Sicán. En Cultura Sicán. Esplendor preincaico de la Costa Norte (Izumi Shimada, pp. 93-106). Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú.

Franco, R., & Gálvez, C. (2014). Contextos Funerarios de Transición y Lambayeque en el Complejo el Brujo, Valle Chicama. Cultura Lambayeque. En el contexto de la costa norte del Perú, actas del primer y segundo coloquio, 139-165.

Franco, R., Gálvez, C., & Vásquez, S. (2007). El Brujo: Practicas Funerarias Post Mochicas [Inédito].

Gálvez, C., & Castañeda, J. (2014). Arquitectura Post—Mochica elaborada en Tierra: La evidencia del valle de Chicama. En Cultura Lambayeque. En el contexto norte de la costa del Perú. (Julio Fernández y Carlos Wester, pp. 397-418).

Goldstein, D. (2014). La administración Sicán de los recursos naturales: Bosques y combustibles de madera. En Cultura Sicán. Esplendor preincaico de la Costa Norte (Izumi Shimada, pp. 147-158). Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú.

Huckleberry, G., Caramanica, A., & Quilter, J. (2018). Dating the Ascope Canal System: Competition for Water during the Late Intermediate Period in the Chicama Valley, North Coast of Peru. Journal of Field Archaeology, 43(1), 17-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2017.1384662

Kosok, P. (1965). Life, Land, and Water in Ancient Peru: Vol. null (null, Ed.).

Larco, R. (1948). Cronología arqueológica del norte del Perú. Sociedad Geográfica Americana.

Mujica, E. (2007). El Brujo. Huaca Cao, Centro Ceremonial Moche en el Valle de Chicama (Elías Mujica). Fundación Augusto N. Wiese.

Prieto, G. (2014). El Fenómeno Lambayeque en San José de Moro, valle de Jequetepeque: Una perspectiva desde el valle vecino. En Cultura Lambayeque. En el contexto norte de la costa del Perú. (Julio Fernández y Carlos Wester, pp. 107-138).

Rucabado, J., & Castillo, L. J. (2003). El periodo Transicional en San José de Moro. En Moche: Hacia el final del milenio (Santiago Uceda y Elias Mujica, Vol. 2, pp. 15-42).

Segura, R., & Shimada, I. (2014). La interacción Sican Medio-costa central, hacia 1000 d. C. En Cultura Sicán. Esplendor preincaico de la Costa Norte (Izumi Shimada, pp. 303-322). Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú.

Shimada, I. (1995). Cultura Sicán. Dios, Poder y Riqueza en las Costa Norte del Perú. Fundación del Banco Continental para el Fomento de la educacion y cultura, EDUCABANCO. https://fundacionbbva.pe/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/libro_000051.pdf

Shimada, I. (2014). Detrás de la Máscara de Oro: La cultura Sicán. En Cultura Sicán. Esplendor preincaico de la Costa Norte (Izumi Shimada, pp. 15-90). Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú.

Wester, C. (2018). Personajes de élite en Chornancap: Una nueva visión de la cultura Lambayeque (Primera edición). Perú, Ministerio de Cultura, Viceministerio de Patrimonia Cultural e Industrias Culturales, Proyecto Especial Naylamp-Lambayeque, Unidad Ejecutara No 005.

Researchers , outstanding news