- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Andean Foods: Ají Amarillo

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Leslie Zúñiga y José Alva

“Of the vegetables that produce their fruit on their branches, there is the ají pepper, which, second to corn, is the most widely used and esteemed plant among the Indians from those that they found in this land” (Cobo 1964 [1656]: 172).

Ají is the fruit used as a spice that is the most appreciated in Andean cuisine since times immemorial. The esteem enjoyed by ají was such that it competed with corn consumption [1]. Throughout this note, we shall review the history of ají and its varieties, among which we shall highlight ají amarillo (yellow ají) as one of the most popular ingredients in contemporary Peruvian cuisine.

The Ajís from El Brujo and in History

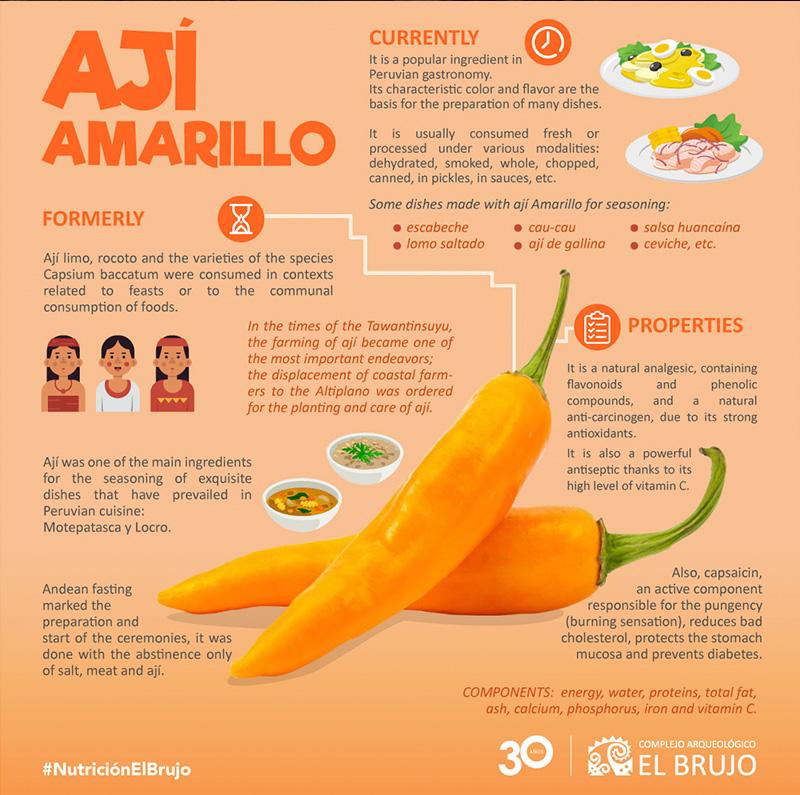

In Huaca Prieta and in the Paredones sector, located in the southernmost part of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex, there is the most ancient evidence of ají consumption, with a notable variety of species, among which are ají limo, rocoto and the varieties of the species Capsicum baccatum. The latter had an increasing consumption throughout the Archaic period in contexts related to feasts or to the communal consumption of foods [2].

In the times of the Tawantinsuyu, ají farming became one of the most important endeavors. The Inca state ordered the displacement of coastal farmers for the planting and care of ají in the Altiplano region (Andean Plateau) [3].

In the History of the New World by father Bernabé Cobo it is said that in the times of the Incas ají was one of the main ingredients for seasoning exquisite dishes, whose names and preparations have prevailed in Peruvian cuisine [4]:

Motepatasca: A stew made with cooked corn, herbs and ají.

Locro: Ragout of charqui (dehydrated meat), chuño (freeze-dried potato), potatoes, vegetables and plenty of ají.

Additionally to its nutritious use, ancient Peruvians incorporated ají into their ritual practices.

Andean fasting, which marked the preparation for the start of the ceremonies, was done with the abstinence of only salt, meat and ají. Moreover, the burning of offerings for the ending of the ceremonies included tossing ají onto the fire [4].

With the passage of time, the different varieties of ají were incorporated into the gastronomy of the colony and the republican epoch, this being one of the ingredients that participated in the culinary culture-mixing that took place between the XVI and XIX centuries, characterized by the integration and migration of populations foreign to the Peruvian territory.

Ají Amarillo

Among the diversity of the ají that are most consumed in contemporary Peru there is ají amarillo (Capsicum baccatum var pedelum). This ají is a popular ingredient within the current Peruvian gastronomy. Its characteristic color and flavor are the basis for the preparation of a variety of dishes and sauces. It is usually consumed fresh or processed under various modalities: dehydrated or dried (ají mirasol), smoked, whole, chopped, canned, in pickles, in sauces, etc.

Escabeche, lomo saltado, cau-cau, ajiaco, locro, ají de gallina, causa, ceviche, chupe de mariscos, are some of the many dishes that use ají amarillo for seasoning. And let us not forget the emblematic Huancaína sauce, whose main ingredient is our little orange friend.

Medicinal properties and nutritional values

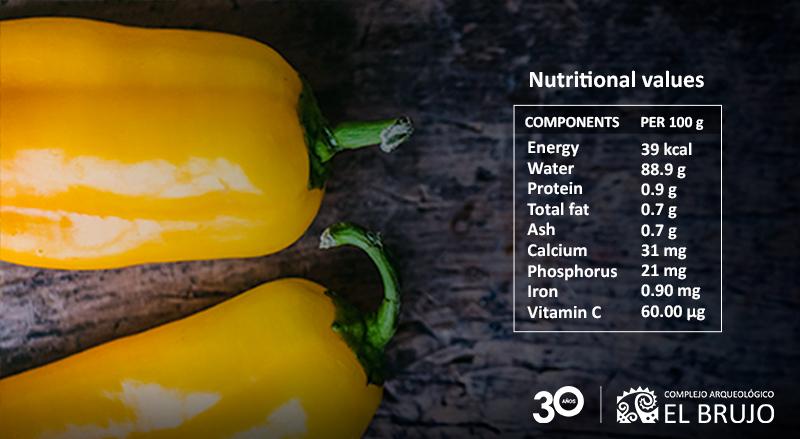

Not only is the great seasoning power of ají amarillo, and the other variants of Capsicum, remarkable, but also its medicinal properties. Thus, we note that this vegetable is a natural analgesic [5], since it contains flavonoids and phenolic components; it is anti-carcinogenic, due to its powerful antioxidants [6] and it is a powerful antiseptic thanks to its high levels of vitamin C [7]. Also, Capsaicin, an active component that is responsible for the pungency (burning sensation), reduces bad cholesterol [8]), it protects the stomach mucosa [9] and prevents diabetes [10].

Note: Adapted from “Peruvian tables of food composition”, crafted by Reyes G., María; Gómez-Sánchez P., Iván; Espinoza B., Cecilia. Copyright 2017 by the Ministry of Health, National Institute of Health.

Researchers , outstanding news